Reaping the Harvest: Tools for the Harvest

So you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start?

Sam Knapp built Offbeet Farm, a winter storage farm in interior Alaska, from the ground up. Read on for how he breaks down the options of harvesting tools for both small- or large-scale operations.

Beyond the Root Cellar is the inspiring guide that proves that—with a little ingenuity—the savvy grower can successfully select, harvest, store, and sell vegetables throughout the off-season, providing their family and community the local food they need during winter months.

The following excerpt is from Beyond the Root Cellar by Sam Knapp. It has been adapted for the web.

Featured Image: Harvest conveyors allow crew members harvesting multiple rows to quickly and safely deliver veggies to harvest bins on a trailer without walking back and forth or tossing veggies through the air. Photo courtesy of Martin’s Produce Supplies.

Harvest Tools

While there may be some overlap with other vegetable farms, farms that focus on storage crops usually have specialized tools and equipment to make the harvest easier and faster. Nearly all storage crops are bulky and heavy. Many storage crops grow at least partially underground and must be dug out. Most tools and equipment for harvest either help you dig up crops or move them from place to place more efficiently. Some tools are common to most farms, whereas others are more specific to either small- or large-scale farms.

As storage farms grow and develop, many are on the search for an equipment sweet spot.

The purpose of machinery is almost always to make tasks faster, more efficient, and more ergonomic to workers. Machines come with costs, some obvious and some not, and any farmer should estimate cost savings when considering a new piece of machinery.

- How much does it cost in labor, fuel, time, and so on to do a task currently, and how will that change with the new equipment?

- Are those savings worth the costs of the equipment?

- How much labor is available, and would you rather hire workers or use a faster machine?

- Will the equipment prevent hidden costs, such as future medical bills or loss of physical ability due to injury or overuse?

Machines and equipment should match not only your budget and scale, but also your goals and values.

Cutting tools are found on most every farm, regardless of size. These are simple knives and pruners for cutting and trimming crops in the field. Knife styles are a personal choice. For example, some farmers prefer lettuce- or broccoli-style harvest knives—which have sharpened and squared-off or rounded tips—for cabbages.

A potpourri of harvest knives at Offbeet Farm. The ones with bright orange markings—either paint or flagging—are much more likely to be found if lost in the field.

Photo courtesy of Phil Knapp.

These allow workers to cut through stalks with a pushing motion that utilizes the shoulder rather than the wrist. Many farmers also prefer pruning shears over knives for harvesting winter squash and pumpkins. Even if stems aren’t corky, there’s no telling what you might hit after cutting through a resistant squash stalk (another squash, irrigation lines, or worse).

With both knives and pruners, it’s important to keep them sharp, and I usually carry a sharpener in my back pocket. Sharp knives and pruners are safer to use than dull ones, and they make cleaner cuts less likely to attract pathogens in storage.

It’s also a good idea to attach bright colors to these small and easily-lost tools! Whether that means spray paint, tape, or flagging, you’ll thank yourself for doing this when a tool suddenly disappears.

There are several tools that help loosen soil so that belowground crops are easier to pull by hand later.

At the hand scale, there are both digging forks and broadforks. Digging forks, also called spading forks, are great tools for many tasks, from loosening carrots to digging potatoes. They’re easy to use and inexpensive, but they’re relatively slow.

Broadforks are a faster hand-scale option. They’re usually two to three times wider than traditional digging forks, but they often cost considerably more. Although you can use regular broadforks for harvesting, the harvest-specific broadforks are best. Their tines are closer together—to reduce the risk of tines slipping through the soil and damaging crops—and narrower, so they’re lighter and easier to push into the ground.

The go-to tools on larger, tractor-scale farms are undercutter bars, also called bed lifters. These are simple, relatively inexpensive implements mounted to the three-point hitch on full-sized tractors. The “bar” is pulled through the soil at depths of 12 to 16 inches to lift and loosen the soil above (hence the name).

Many farms without more specialized harvesting equipment run undercutter bars beneath their deep-rooted crops to make hand-pulling easier and faster. I’ve also heard of farms using subsoilers to loosen soil around crops like garlic, but undercutter bars are far more common. Unfortunately, two-wheeled tractors don’t have enough weight or traction to pull undercutter bars through the soil. Many have tried it, and many have failed.

Tractor-Run Harvesters

Both for two-wheeled and full-sized tractors, there are more specific harvesting implements designed for single or multiple crops, though there are fewer options for two-wheeled tractors. Both BCS and Aldo Biagioli sell relatively inexpensive root-digging plows for two-wheeled tractors, but the general consensus is that these apply mainly to potatoes. You’ll need to add weight to the twowheeled tractors—usually wheel weights—and the diggers go only as deep as the soil has recently been worked.

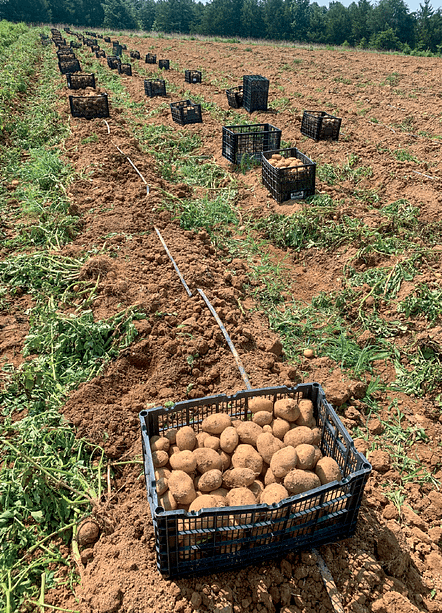

The potato harvest at Open Door Farm in Cedar Grove, North Carolina, assisted by a single-row potato digger.

Photo courtesy of Jillian Mickens.

Crops such as sweet potatoes, carrots, and daikon radishes are often rooted too deeply and are damaged by these diggers, whereas more shallowly rooted crops such as beets, turnips, and onions don’t require enough soil-loosening to warrant such a tool. These implements might be useful for garlic and sunchokes if driven alongside the rows.

There are also PTO-powered potato diggers for walk-behind tractors, but they, too, have a depth limitation. The manufacturers suggest that you plant potatoes shallowly and rely on hilling to effectively use these harvesters.

Potato diggers for full-sized tractors are some of the most popular harvesting implements out there. They’re relatively inexpensive and simple to run and repair, often lacking any hydraulic components. Storage farmers use them for potatoes, of course, but they’re also effective at harvesting sweet potatoes and sunchokes.

Most farmers I’ve talked to use Spedo-brand diggers. The simplest and cheapest model is a one-row shaker, which sieves out soil and lifts tubers to the surface. It’s similar to the walk-behind digger but can dig up to 12 inches into unhilled soil. That said, both weeds and wet soils tend to thwart this style of harvester.

As one farmer I spoke with reported, the vibrating diggers struggle to separate soil clumps and end up slicing through sections of wet or weedy soil without actually sifting out the spuds. Spedo (and other companies) also sell chain-style diggers, which use chain conveyors to remove soil from around tubers before depositing them on the soil surface.

Chain diggers are more expensive but can sometimes harvest multiple rows at once and work in a wider variety of soil conditions than shaker-style diggers. There are also larger chain-style harvesters that incorporate features such as sorting areas for workers and the ability to carry and fill bulk pallet bins.

Carrots dangle from the harvest belts of a Scott Viner on Food Farm in Wrenshall, Minnesota.

Photo courtesy of Janaki Fisher-Merritt.

Scott Viner Harvesters

The FMC Scott Viner (commonly called the Scott Viner) is by far the most popular root harvester among small-scale storage farmers. Every storage farmer I talked to who mechanically harvested their carrots, beets, and other roots either had used or was currently using a Scott Viner. Originally designed for beet harvesting in the 1930s, Scott Viners are used today for harvesting carrots, beets, radishes, parsnips, turnips, and even rutabagas, depending on modifications to the machine.

Their popularity is due in part to their functionality, but also to their price. Because they’re no longer manufactured and most are old, they’re relatively cheap as far as implements go. The newest machine I could find for sale was made in the 1970s.

That said, they’re relatively simple machines, and if a farmer is willing to replace hydraulic lines, grease or replace bearings, and resurface rusty metal, older Scott Viners do their jobs admirably. They’re also versatile and can be modified to work within a specific farm’s systems.

Scott Viners work by running a digging shoe beneath a row of roots—let’s say carrots for example. At the same time, a set of rubber belts pinch carrot tops just above the crowns and lift them from the ground. The belts run backward and up, the carrots dangling by their tops, toward a knife that cuts the tops and drops the carrots onto a chain conveyor. The tops are shot out the back of the machine while the roots are conveyed away, the soil bouncing through the chains. Some farmers drive a wagon alongside the harvester for the carrots to drop into containers, while others modify the conveyor to spit carrots out behind the machine.

Scott Viners and similar harvesters can turbocharge the rate of harvest for deep-rooted crops like carrots. Several farmers reported that one fast worker can harvest between 200 and 250 pounds of carrots per hour on a clean bed that’s been loosened by an undercutter bar. With a well-functioning Scott Viner, the typical rate increases to 2,500 to 3,000 pounds per hour.

However, running the Scott Viner might require three to four people: one to drive the tractor, one to operate the Scott Viner, one to funnel carrots into bins, and one to pull a wagon alongside the machine. Scott Viners also require relatively clean and dry fields. Weeds tend to block up the topping mechanism and can make it difficult to see and align the machine to the row. The machine also has trouble staying aligned and pulling roots from heavy, wet soils. Many farmers running Scott Viners or similar machines shift their harvest dates to increase their chances for dry weather.

There are newer machines similar to FMC Scott Viners that require fewer people to operate. One popular example is from the Canadian company Univerco. Their smallest root harvester can be operated by a single person who drives the tractor and operates the machine while the implement fills bulk pallet bins. These machines can also offload full bins with a hydraulic platform lift. Although such machines are more expensive than Scott Viners, they typically run with fewer mechanical issues and have lower labor costs to operate.

Materials Handling at Harvest

Harvest is usually the first point in the storage process when materials handling becomes an issue. Storage crops are generally bulkier, heavier, and less valuable by weight than their fresh-marketed cousins. To be a successful storage farmer, you need to be able to lift and move heavy objects from place to place quickly and safely.

I like to think of the process of moving crops out of the field and into storage like a river system.

Furthest upstream are the small drainages and tributaries collecting water from small swales and ravines. These are like veggies passing through the hands of workers as they harvest small sections of the field. As water moves downhill, the small streams join together to form larger rivers. These are like veggies from individual sections of the field aggregated together for processing steps such as washing or curing. Eventually, more and more tributaries join to form large and powerful rivers that drain entire watersheds. After processing, we place veggies inside our largest bulk containers and funnel them inside our storage spaces where they remain for weeks to months. What starts as a trickle becomes a mighty river of vegetables collected in one place.

There are two main pieces to the puzzle of materials handling at harvest (and in general): the containers used to hold crops and the equipment used to move them.

Containers and handling equipment are linked; the containers you use influence your options for handling equipment, and vice versa. This relationship also extends to the equipment and methods used for processing steps before storage.

The harvest cart at Offbeet Farm is the main way we move veggies from the field to the wash station. Photo courtesy of Phil Knapp.

Let’s start with options for materials-handling equipment.

At the hand scale are things like wheelbarrows and carts. At Offbeet Farm, we mostly use a modified garden cart to transport veggies from the field to the wash station. This allows us to move about 200 pounds at a time with minimal effort, so long as loads are well balanced.

Carts and wheelbarrows usually have limitations for both the weight and height (when stacking multiple containers) because the user tips them at an angle in addition to lifting them, and this is especially true when using them on hills. There are some innovative designs for well-balanced and ergonomic carts, such as those popularized by Josh Volk of Slow Hand Farm.

Small trailers pulled by walk-behind tractors, ATVs, lawnmowers, pickup trucks, and full-sized tractors are good options for carrying larger, heavier loads than is possible with hand carts. However, trailers are less nimble than carts, requiring more space to turn around and more skill to run in reverse. Pickup trucks, or any vehicles with beds, are also great options for transporting veggies out of the field. Many farms outfit their tractors or skid steers with forks to either move large pallets or bulk bins throughout the field or to stack the bins on trailers for hauling.

Containers for harvesting and transporting veggies are usually either very small or very large.

At the small end, many farms use 5-gallon buckets or bulb crates for harvesting. That’s because these containers are relatively cheap and easily moved, stored, and lifted. I personally advocate for using small harvest containers because it places physical limits on how much you can lift at any one time. Even some large storage farms use 5-gallon buckets as direct harvest containers and transfer the veggies into larger containers later.

Larger harvest containers are usually bulk, pallet-sized bins such as plastic macrobins. Workers can harvest directly into bulk bins if the bins are driven through the field on forks, or they can empty smaller containers into nearby bulk bins. These are the go-to containers for farms using mechanical harvesters and time-saving equipment like harvest conveyors. Some farmers use the same containers for both harvest and storage, while others have specific containers for each task.

While your harvest containers will influence your options for handling equipment and vice versa, this relationship isn’t equal.

I suggest prioritizing handling equipment when considering upgrades. Larger and stronger handling equipment will save you time by reducing the number of trips needed to remove your crops from the field, and, most importantly, large handling equipment can accommodate any container size.

This isn’t true in the other direction; large containers aren’t compatible with small-scale handling tools. Additionally, handling equipment upgrades are often less expensive than container upgrades. This is especially true when purchasing bulk storage bins, which can be several hundred dollars each. Of course, upgrading both containers and handling tools simultaneously is fine, but if you’re limited by your budget, purchase better handling equipment first.

Harvest Conveyors

Harvest conveyors are useful for more than just storage crops but are very popular among farmers growing lots of cabbage or winter squash. The machines consist of boom arms extending 20 feet or more off a harvest trailer with a conveyor belt that moves crops from the field to the trailer. Usually, several workers harvest along field rows as the conveyor moves slowly down the field. One extra person is required to run the conveyor and direct veggies coming off it into containers. The beauty of this system is that workers don’t need to carry (or toss, as many farm crews do) squash or cabbage heads between the rows and the trailer or containers.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Nothing says “spring” like a fresh, foraged meal! Savor the flavors of the season with this Milkweed Bud Pizza recipe.

Read MoreOxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreSo you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start? Learn how to break down the options of harvesting tools!

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read More