How Cattle Grazing Improves Soil Diversity: Saving Our Soil

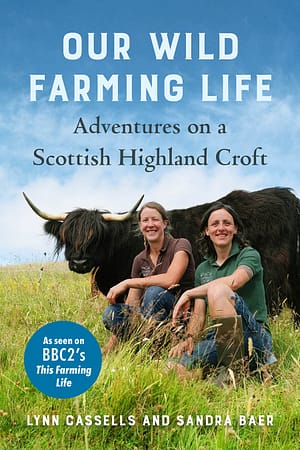

In Our Wild Farming Life, Lynn Cassells and Sandra Baer recount their experiences as they create Lynbreck Croft—a regenerative Scottish farm rooted in local food and community. As they build their farm, Cassells and Baer bring new livestock to their land and learn techniques to help them truly understand how they can farm in harmony with nature.

While all the animals on Lynbreck Croft taught them important life lessons over time, Highland cattle were perhaps the most impactful. Not only are these Scottish cattle exceptionally beautiful, but when raised properly they can drastically improve the state of our soil and our land.

The following is an excerpt from Our Wild Farming Life by Sandra Baer and Lynn Cassells. It has been adapted for the web.

All photos by Sandra Angers Blondin.

Highland Cattle: More Than A Hobby

They eat a wide range of vegetation, from grasses and wildflowers to shrubs and tree leaves, and are naturally built for all weather conditions, enabling them to be outside 365 days of the year. Their beauty and iconic image can often do them a disservice, sometimes having the association of being ‘hobby’ cattle for ‘hobby’ farmers and demoted to being the face of toffee bars and advertising campaigns.

However, to us, these animals were much more than just a pretty face, acknowledging their natural resilience and strength and seeing the perfection in their suitability to become a part of our team at Lynbreck.

In my previous job with the Borders Forest Trust, I had been fortunate to meet a gentleman called Roy Dennis, a virtual giant in the world of conservation and a pioneer of habitat restoration, mammal and bird reintroductions. Roy had previously lived and worked in Abernethy Forest and in 1998 published a paper entitled ‘The Importance of Traditional Cattle for Woodland Biodiversity in the Scottish Highlands’, which we came across in our early Lynbreck days.

He wrote about the potential benefits of keeping cattle that could fill a niche in our natural ecology, the importance of dunging for soil health and insects, the creation of different habitats as a result of their presence and movements through the landscape, and the recycling of plant material through their grazing patterns and preferences. Roy made a compelling case for the use of hardy, native breed cattle in small numbers at low densities that would also ultimately provide exceptionally high-quality beef that could be marketed and sold at a premium.

Adopting A Natural Cattle Grazing System

We would mitigate against the ground becoming too broken up and mucky by carrying low animal numbers on a grassland where the plants had deep root systems, able to hold the weight of the lighter-framed Highland cattle. And the plan meant avoiding any unnecessary soil compaction, a condition caused by repeatedly carrying heavy weights like large groups of heavy animals or vehicles, leading to the oxygen literally being squeezed out of the soil and rendering the ground lifeless.

In contrast, our aim was to have light, crumbly, aerated soil that, when the rains came, could literally soak up water like a sponge, water being an essential natural resource that we wanted to store in as many ways as possible for the plants above.

And the most important part would be ensuring that the area where the cattle had just grazed would be allowed sufficient time to rest and recover. When a plant is grazed by an animal, it needs time to fully regrow, and if it is not given that time and is grazed again, it draws on root reserve energy to keep going, a process called overgrazing. When this happens repeatedly, the plant will eventually become stunted, producing less biomass and it will ultimately die. Through careful planning, we could avoid that, helping to keep our pasture healthy and vigorous.

Our responsibility would be to oversee those movements, which, in the summertime would mostly be daily, factoring in considerations such as availability and diversity of forage, water and shelter, as well as seasonal things like calving and weaning. This consistent interaction would also give us the opportunity to regularly monitor their grazing impact, making changes to our plan when needed, building knowledge and experience as we went.

Our now go-to animal author Fred Provenza claims that herbivores, if given the chance, will graze on up to fifty different plant species in a single day, based on their need for specific nutrients and minerals. Our pastures had the beginnings of a diverse flora forage platter for the cattle to pick through and, we hoped in time, their work would help to grow the diversity of what they could choose from.

Bale Cattle Grazing: It’s All In The Hay

But, as autumn turned to winter and the last of the standing grass was grazed, we unwrapped our first hay bale, unleashing the warming smell of summer grasses and wildflowers and taking armfuls out to our fold who were starting to vocalise their discontent with the forage scraps left in the field.

Ronnie, in particular, would look at us with immense discontent. She’s always had a healthy appetite, her frame perhaps carrying a touch more weight than the others as she certainly enjoys her food, yet another attribute that just became part of Ronnie. They all tucked in with such delight as we stood back, watching them eat every last stalk before collapsing in heaps onto the hard, frosty ground, chewing the cud with utter contentment. It was from this point on, when we watched them lie down with full bellies that we affectionally referred to them as the ‘lumps’.

We began to use our twice daily hay allocation to continue our regular cattle moves, feeding them in different locations, but this time in much larger paddocks so that they would always have access to shelter from trees should a winter storm come in. Because the cattle wouldn’t be in any one place for a long time, this helped to avoid our ground getting muddy and compacted. Any scraps of hay that they didn’t eat would simply break down, feeding the soil as dislodged seedheads were trodden into the ground, planting them to sprout new growth in spring.

We also started to experiment with a technique called bale grazing, a tactic of simply putting a hay bale in a spot in the field that we’d identified as needing a bit of a fertility boost, taking off the netting that holds the layers in place and letting the cattle eat from it directly. Once prepared, we would bring the cattle to the bale, a time of obvious excitement as the boys would head-butt it or the girls would dig their horns straight into the side, sometimes flipping the bale, before they settled down to feast.

It would take our fold between two to three days to finish their ‘all you can eat’ buffet where the end result was a large circular matt of hay a few inches thick. We had to fight the urge to rake the leftover hay off, subduing doubts sowed by others that the ‘waste’ would ‘smother’ the grass in the summertime, knowing that we had to leave this ‘wasted’ hay with patches of dung to break down into the soil.

The following summer, these patches were transformed into lush and diverse forage, buzzing with insect life as little field voles utilised the new cover to move around their territory. Through this very simple technique, we were slowly starting to increase the amount of diverse grazing for our Highlanders, now seeing ‘hay waste’ as soil food and a trickle investment into the prospering bank of soil.

Recommended Reads

The Power of Traditional Herding & Grazing: Bringing Back Balance

Recent Articles

What’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read MoreEver heard the phrase, “always follow your nose?” As it turns out, this is a good rule of thumb when it comes to chicken manure. Composting chicken manure in deep litter helps build better chicken health, reduce labor, and retain most of the nutrients for your garden. The following is an excerpt from The Small-Scale Poultry…

Read MoreIn her book, The Art of Science and Grazing, nationally known grazing consultant Sarah Flack identifies the key principles and practices necessary for farmers to design, and manage, successful grazing systems. This book is an essential guide for ruminant farmers who want to crate grazing systems that meet the needs of their livestock, pasture plants,…

Read MoreThis long-lived perennial legume is used for forage and erosion control. Kudzu is edible with many medicinal uses and other applications. Pollinators of all kinds love its prodigious lavender blooms!

Read MoreAre you ready to get a jump-start on the gardening season? With a cold frame, you can get started now. A cold frame harnesses the sun’s heat before it’s warm enough to let unprotected seedlings growing outside. Essentially, it consists of a garden bed surrounded by an angled frame and covered with a pane of…

Read More