Milkweed Bud Pizza with Bacon and Pickled Turnips

Nothing says “spring” like a fresh, foraged meal! Savor the flavors of the season with this recipe.

For most people common milkweed is just that, common, and a weed. Fortunately, foragers have an unusual ally: the monarch butterfly. Increasingly, people are becoming aware of the association between the beleaguered butterflies and milkweed.

Whether you cultivate or forage milkweed for the pizza, it will taste just as good!

The following excerpt is from Forage, Harvest, Feast by Marie Viljoen. It has been adapted for the web.

(All photos courtesy of Marie Viljoen unless otherwise noted.)

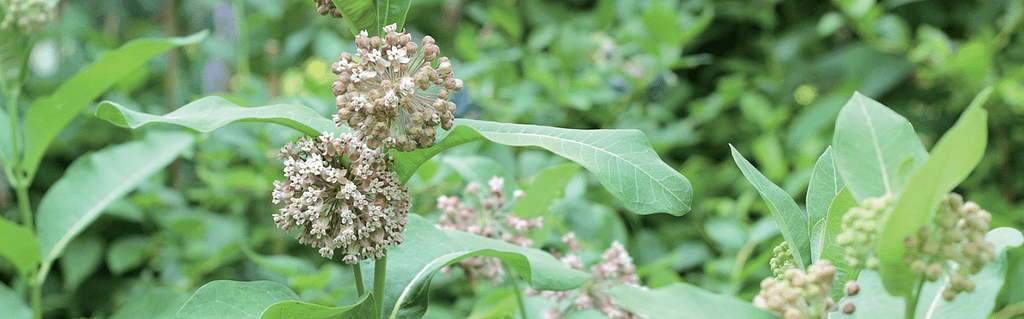

Common Milkweed

OTHER COMMON NAMES: Butterfly flower silkweed, cotton weed

BOTANICAL NAME: Asclepias syriaca

STATUS: Indigenous perennial, mostly east of the Rockies

WHERE: Open ground, farmlands, highwayshoulders, gardens

SEASON: Early spring to late summer

USE: Vegetable, aromatic

PARTS USED: Shoots, tender stems, buds, flowers, and young pods

GROW? Yes, if you do not mind unruliness

TASTES LIKE: Fava bean meets asparagus (but not really)

In North America we have a largesse of indigenous edible plants that heralds the edible year. Common milkweed is the most generous. Every stage of the plant’s aboveground growth is edible, from its downy spring shoots, through early-summer stems and buds, midsummer flowers, and late-summer seedpods.

But for most people common milkweed is just that, common, and a weed. Its colonies, spreading via determined stolons underground, often interfere with the orderly plans of gardeners, farmers, landowners, and highway managers, who view it as a nuisance plant and kill or mow it. It usually falls victim to herbicides, since digging it out is relatively ineffective.

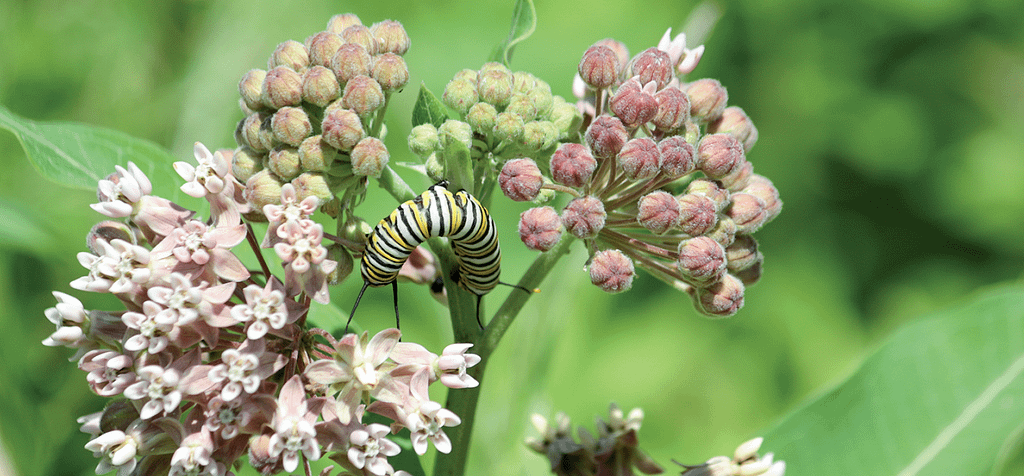

Fortunately, foragers have an unusual ally (and the converse is true, too): the monarch butterfly. Increasingly, interested citizens of the twenty-first century are becoming aware of the association between the beleaguered butterflies and milkweed. Monarch butterfly larvae (caterpillars) only feed on milkweed. This has led to a growing advocacy for the planting and preserving of milkweed populations.

Dozens of species of milkweed are indigenous to North America.

While some are reputedly toxic, ethnobotanical records show that many Native Americans used several species for food, including Asclepias syriaca (our common milkweed), A. speciosa, A. incarnata, A. viridiflora, and A. verticillata. Most modern foragers are acquainted with the first. I would happily eat the others, if I could find them readily.

Common milkweed’s earliest stage of eating is the young shoot whose leaves have not yet infurled.

They appear in early spring and closely resemble a toxic plant called dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum). The shoots of dogbane and common milkweed look so similar (and both bleed latex) that this confusion may have led to the myth promulgated by Euell Gibbons, who popularized American foraging in 1962 in his seminal book Stalking the Wild Asparagus. His advice to boil the milkweed three times to dispel “the extremely bitter principle” has been repeated by countless subsequent writers and obeyed by legions of obedient foragers. I did it, too, the first time I ate the vegetable.

But common milkweed is not bitter, not even when raw.

Dogbane is. Sam Thayer’s seminal book The Forager’s Harvest contains six pages of enlightening and entertaining reading on this subject. He deserves an award for dissolving this widespread untruism that common milkweed itself is toxic unless boiled to death.

Driving in the Catskills one spring day, my husband stepped on the brakes as I waved wildly at a green field (this happens quite often). The field was filled with cows, green grass, and young common milkweed, already in leaf. The farmer was nearby (castrating some very unhappy pigs) and managed to keep a reasonably straight face when this city person asked him if she could collect the milkweed in his field. “Take it all,” he said, and went back to the vocal pigs.

In a borrowed pair of rubber boots I waded through a quagmire of cowpats to emerge in the milkweed patch. I picked a huge bundleful, and we drove home to the city, thinking quite unhappily about pork chops. These young stalks may be my favorite part of the plant. They can be eaten in any way that you would prepare asparagus (though common milkweed’s flavor is essentially its own). I remove and reserve their tender leaves, serving the supple and elegant stems alone. After blanching the young leaves, I purée them and freeze to keep for green tarts, pizzas, and dumplings. Their texture is similar to fava beans.

In early summer, when local strawberries are ripe, milkweed buds form, looking a little like fuzzy broccolini. Their stems are still very tender, and the uppermost leaves are still good to eat, once cooked. Again, all they need is a quick blanch before cooking them any way you like. They are memorably delicious.

A few weeks later the heavy umbels of powerfully aromatic flowers open. Their perfume, caught in a fermented cordial or syrup (coldinfused or you lose most of the fragrance), makes a drink that tells of a summer field under a blue June sky. It mixes beautifully with gin and lime juice, or Prosecco, or sparkling water, and can be the inspiration for summer popsicles, sorbets, and syllabubs. Fermented flowers create a unique and gorgeously lilac vinegar.

In late summer the young, prehistoriclooking seedpods are an exceptional vegetable, blanched for a few seconds and then pan-roasted or sautéed until tender. They are reminiscent of okra but not as mucilaginous. You can also slit the larger pods to remove the immature white silk inside, eating only this morsel, briefly cooked—it is soft and startlingly sweet, with a flavor like the flowers’ scent. The leftover skins can be deep-fried to make a crisp botanical chicharrón.

Common milkweed’s usefulness in so many stages suggests that it could be grown as a bona fide crop.

It is a plant we should be nurturing for a host of reasons, not least of which is its cash potential to open-minded growers. And my personal feeling is that everything above can be applied not just to the commonly foraged Asclepias syriaca but also to the other milkweed species used by Native Americans. I have not personally eaten them, but others have, and the ethnobotanical record is significant.

Because I live in New York City, where common milkweed colonies compete with and always lose to development, I now grow my own (along with a few other species for pollinators). Some of my plants were ordered online; others came from a feral milkweed colony around the corner on a construction site. The home’s new owner allowed me to dig them up in springtime. And yes, the Brooklyn monarchs have found them. Ideally, it is better to grow and buy plants from local stock, and I have no doubt that more nurseries will be stocking this milkweed. The edible word continues to spread, in tandem with the burgeoning awareness that growing indigenous plants helps boost and support local biodiversity. What we plant matters.

CULTIVATION TIPS

USDA Hardiness Zones 4–9

Common milkweed seeds are increasingly available. Before being sown, they need to be cold-stratified to spur germination.

Planting young plants from nurseries or transplanting mature plants is a quicker and easier option. Common milkweed resents being transplanted midseason. The aboveground parts will go into shock and drop their leaves, but the roots and runners will remain busy underground. Very, very busy.

The following spring shoots will pop up where you least expect them. This plant will never grow in a neat vegetable row, which may present a challenge to growing it as a crop, as it would have to be managed very differently from well-behaved corn. In a garden, grow this lovely plant where it has room to move. And it will.

Tolerant of various soils, as long as they are well drained, common milkweed does require sun in its growing season, six hours or more being ideal. My own colony manages with much less (well, none) in the months from late fall through spring, but in summer it gets its full dose, and it grows prolifically, topping out at 6 feet tall.

Caution

In its shoot stage common milkweed has a poisonous lookalike: dogbane (Apocynum canabinum). How to tell them apart? Milkweed shoots and leaf undersides are slightly furry; dogbane’s are smooth. Milkweed stalks are often hollow (but not always, when young); dogbane stems are solid. Milkweed’s sap is mild to sweet; dogbane’s is bitter (a tiny taste won’t hurt).

Common Milkweed Bud Pizza with Bacon and Pickled Turnips

Makes one 14-inch (35 cm) pizza

Scattering milkweed buds across a pizza makes the few seem like many. The pickled turnips add last-minute crunch and brightness. High-flavor pantry basics like Lacto-Fermented Garlic Mustard and Ramp Leaf Salt send it over the top. Other tricks? Yes. Good bacon. My go-to bacon is nitrate-free, smoked, and fairly thickly sliced. Roasting it in the oven keeps it nice and flat.

Pizza Dough

- 1 tablespoon dry yeast

- 1 teaspoon sugar

- 3/4 cup (190 ml) warm water

- 2 cups (240 g) all-purpose flour

- 3/4 teaspoon salt

- 3 tablespoons olive oil

Topping

- 3 ounces (85 g) common milkweed buds

- 1 jalapeño pepper

- 1 tablespoon Common Milkweed Flower Vinegar

- 4 slices bacon

- 2 medium balls (8 ounces/227 g, total) fresh mozzarella

- 6 young Japanese turnips (substitute radishes)

- 1 tablespoon salt

- 2 tablespoons Lacto-Fermented Garlic Mustard

- Ramp Leaf Salt

For the dough

Preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C).

Punch down the risen dough. Oil a large pizza pan or baking sheet. Hold the dough up in front of you in both hands and work your way around it, holding it by the upper edge and letting the rest hang down as you move it counterclockwise (if you are right-handed). Keep moving steadily and quickly and gravity will stretch it. If one side starts to go rogue and stretches too much, lay it flat on your prepared sheet and push the dough out toward the pan edges from the middle, using your knuckles. When you have an even circle, cover the dough and allow it to rest.

For the topping:

Bring a pot of water to a boil and blanch the milkweed for 1 minute. Drain, refresh, and roll up in a kitchen towel to dry Slice the jalapeño very thinly and place in a small bowl with the vinegar. Lay the bacon on a baking sheet or in a skillet and roast in the hot oven for about 12 to 15 minutes, until it has begun to color at the edges. Drain the fat and scoop the bacon onto a paper towel. Cut each strip into three or four pieces.

Increase the oven heat to 550°F (290°C).

Tear about ten even chunks from the mozzarella and distribute them evenly across the pizza. Lay the blanched milkweed buds on top of pieces of cheese. Scatter the drained jalapeño slices across the pizza. Add the bacon last.

Slide the pizza into the very hot oven and cook for about 25 to 30 minutes, until the edges of the pie are blistering. While the pizza is baking, cut the turnips or radishes in quarters, keeping some green stems, and lay them in a small bowl. Douse them with the 1 tablespoon of salt and massage it in. Just before removing the cooked pizza, rinse them and pat dry.

When the pizza is done, pull it out, slide it onto a cutting board, and top at once with the salt-pickled turnips or radishes. Scatter the Lacto-Fermented Garlic Mustard sparingly over the top. Season lightly with Ramp Leaf Salt.

Slice, and snarf.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Want to spice up your traditional bread recipes? This salt-rising bread recipe by fermentation expert Sandor Ellix Katz has all the simplicity, flavor, and uniqueness you’ve been searching for! The following is an excerpt from Sandor Katz’s Fermentation Journeys by Sandor Ellix Katz. It has been adapted for the web. What Is Salt-Rising Bread? Salt-rising…

Read MoreNothing says “spring” like a fresh, foraged meal! Savor the flavors of the season with this Milkweed Bud Pizza recipe.

Read MoreSo you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start? Learn how to break down the options of harvesting tools!

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read More