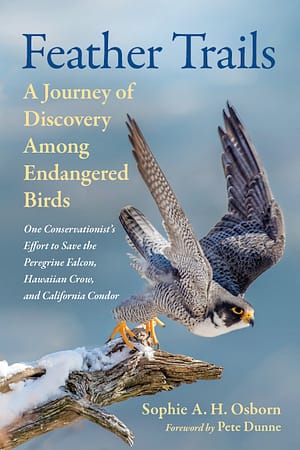

Peregrine Falcons: Then and Now

Peregrine falcons, while known as predators, are essential to our environment. These stunning birds have a rich history, an interesting present, and an uncertain future.

The following is an excerpt from Feather Trails by Sophie A. H. Osborn. It has been adapted for the web.

Who Are Peregrine Falcons?

Though relatively uncommon wherever it occurs, the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) is the most widely distributed, naturally occurring bird species in the world and one of the most widely occurring vertebrate animals on Earth.

A top predator, it is found on every continent except Antarctica and pursues its prey in skies over open habitats that range from windswept tundra to humid tropics, craggy mountains to lush wetlands, surf-pounded seacoasts to inland river canyons, wide-open deserts to sprawling forests, undeveloped maritime islands to densely inhabited cities.1

Wingspan

Some North American Peregrine Falcons travel more than 15,500 miles (approximately 25,000 km) from their northerly breeding grounds to their winter range and back each year.2

Nesting Locations

Despite the peregrine’s adaptability and widespread occurrence, the bird is sparsely distributed throughout its range.

The availability of suitable nest sites (typically a ledge on a high cliff or tall structure) and the territoriality of breeding pairs, whose spacing is itself influenced by the abundance of food, limit its presence.

Perhaps because of the scarcity of suitable nesting locations, peregrines show tremendous fidelity to quality nest sites. In the years before World War II, when peregrine populations were relatively stable, the birds used traditional aeries (nests located in high, inaccessible places) over periods of decades and even centuries in some places.3

Peregrine Falcons in North America

Peregrine Falcons have never been abundant in North America. Indeed, with the exception of several neotropical species whose ranges reach their northern limit in the southern United States, the peregrine may be one of the least numerous raptors (birds of prey) north of Mexico.4

Even before their numbers plummeted beginning in the 1950s, peregrines likely occupied only 7,000 to 10,000 territories in all of North America, ranging from Alaska and the Canadian Arctic to Baja California and the mountains of Mexico.5

So unless one happens to live or work near a nest site, seeing a peregrine is usually rare, and most birders are thrilled to get even a glimpse of this elegant, swift-flying bird.

Human Appreciation

Human appreciation for the peregrine has ebbed and flowed over the course of history. Falcons were worshipped by the ancient Egyptians, who considered the bird to be a sky god and companion of the sun, as well as a symbol of transformation, rebirth, and eternal life.6

Because of their surprisingly docile nature, falcons were captured and trained to hunt for their Egyptian and Chinese keepers as early as 4,000 years ago.

Although falconry was widespread in the Orient, it was not practiced in Britain until the ninth century, and did not become widely prevalent until the early Crusaders—who were introduced to Arab falconers and their ways of training and flying hawks—popularized the sport early in the thirteenth century.7

History of Peregrine Falcons

Europeans dedicated themselves with singular passion to eliminating these predators in the hope that small game animals would thereby flourish.

This malevolent attitude toward predators and the carnage that followed spread to the rest of the globe and continues in many areas to this day, though peregrines eventually received federal protection in North America in the 1970s.8

Persecution of Peregrines

Given their individual scarcity and their widespread distribution, peregrines nevertheless fared better in most areas under this onslaught than did many other raptors.

Although peregrines had long been killed opportunistically, their persecution reached unprecedented levels when Britain sanctioned their systematic extermination during World War II to protect carrier pigeons, which transported messages between military personnel and sometimes met their demise in the talons of hungry falcons.9

More than 600 British peregrines were shot during that time.10 Ever-resilient, though, peregrines in Britain began to recover soon after the wartime persecution ended. But their recovery proved to be short-lived.

Disappearing Peregrine Falcons

Today, it is almost inconceivable that a bird with the peregrine’s cachet and charisma could disappear virtually without notice.

But in an era without mass communication and with far fewer birders combing the landscape, the falcon’s sparse distribution and tendency to nest in remote and inaccessible areas meant that few noticed when the species disappeared from its former haunts.

Ironically, it was the bird’s most vocal detractors who drew the world’s attention to the peregrine’s population declines in the 1950s and who precipitated the eventual discovery of a far more profound threat to the falcon’s well-being than those inflicted by generations of protective gamekeepers, fanatic egg collectors, unethical falconers, and trigger-happy shooters.

The Falcon: Enemy of the Pigeon

Because the peregrine preys on domestic pigeons—descendants of the wild Rock Pigeon—the falcon is not a particular favorite among “pigeon fanciers.” For thousands of years, people worldwide have kept pigeons for food, sport, and entertainment.

Some fanciers race homing pigeons, which are transported long distances then released to fly home to their lofts or coops.

Others breed pigeons for unique flying characteristics, such as rolling, tumbling, or diving. (Such strange behaviors often attract raptors that have evolved to detect debilitated prey by focusing on birds that are not flying like their flockmates.)

Pigeon fanciers include such notables as artist Pablo Picasso, deposed Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, father of evolution Charles Darwin, England’s Queen Elizabeth II, and heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson, who threw his first punch at a thug who callously killed one of ten-year-old Tyson’s beloved pigeons.11

An Unpopular Breed

In both Europe and the United States, extremist fanciers have occasionally expressed their frustration at raptors that target their cherished pigeons, by illegally killing their nemeses.12

In 1960, Ivor George, a Welsh pigeon fancier, expressed his frustration more circumspectly, but with no less passion.

In a television broadcast, he decried peregrines for the large number of homing pigeons they were killing each year in the mining valleys of South Wales—a stronghold for pigeon fanciers—disrupting the fanciers’ sport and destroying the objects of their affection.

Soon after, the fervent fanciers formalized these complaints; they petitioned the British government to remove newly established legal protections for peregrines, claiming that falcons were exacting an unacceptable toll.13

Realizing that it knew little about actual peregrine numbers in Britain, the British Trust for Ornithology responded to the government’s request for information about the bird’s status by hiring biologist Derek Ratcliffe to organize a two-year survey of Britain’s peregrines.14

Peregrine Falcons: A Survey

In areas where birds remained, they often failed to raise young, and their nests sometimes contained broken eggs or eggshell fragments. Ratcliffe had first noted broken eggs in peregrine nests in 1951 and, in the intervening years, had even observed falcons eating their own eggs.

Such baffling behavior and inexplicable egg breakages had never been recorded before. The pigeon fanciers’ woes were superseded by the concerns of scientists and conservationists who scrambled to make sense of the unprecedented population declines of this apex predator.15

A Widespread Decline

Disease and persecution were quickly ruled out as reasons for the widespread decline.

But reports of large numbers of wild birds dying in fields recently sown with insecticide-treated seeds and the subsequent death of two otherwise healthy adult peregrines in Britain in 1961 raised the possibility that newly popular pesticides might be contributing to the falcon’s disappearance.16

The Dangers of Insecticides

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)—a synthetic organochlorine insecticide—was widely used for the first time during World War II to prevent the spread of insect-borne diseases. DDT was subsequently used in increasing amounts to control agricultural and forest insects.

More toxic to mammals than DDT was, the related cyclodiene insecticides (such as aldrin and dieldrin) were introduced into British agriculture around 1955 and were also quickly embraced by farmers.

These newest chemicals were soon found in the tissues of dead or convulsing birds collected from freshly sown fields. Birds that were experimentally dosed with these same pesticides in the lab died in a similarly convulsive manner.17

Peregrine Falcons and Insecticides

European animals that preyed on wild seed–eating birds—sparrowhawks, Common Kestrels, Tawny Owls, foxes, and even domestic cats—were also found dead on or near the same fields as their poisoned prey.

That the Peregrine Falcon, which often nested far from agricultural lands, might similarly be poisoned by preying on sickened birds began to seem possible when an addled peregrine egg was analyzed for chemicals for the first time in 1961 and found to contain small amounts of dieldrin, dichlorodiphe-nyldichlorethylene (DDE—a breakdown product of DDT), and other organochlorine pesticides.

It was the first direct evidence that peregrines could accumulate pesticide residues from eating contaminated prey.18

Notes

-

C. M. White et al., “Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus),” in Birds of North America online, eds. A. Poole and F. Gill (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2002), https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.660.

-

White et al., “Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus).”

-

J. J. Hickey, “Eastern Population of the Duck Hawk,” Auk 59, no. 2 (1942): 176–204, https://doi.org/10.2307/4079550; R. M. Bond, “The Peregrine Population of Western North America,” Condor 48, no. 3 (1946): 101–16, https://doi.org/10.2307/1364462; D. Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed. (T & A D Poyser, Ltd, 1993); White et al., “Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus).”

-

T. Cade, “Life History Traits of the Peregrine in Relation to Recovery,” in Return of the Peregrine, 2–11.

-

L. F. Kiff, “Commentary: Changes in the Status of the Peregrine in North America: An Overview,” in Peregrine Falcon Populations: Their Management and Recovery, eds. T. J. Cade et al. (The Peregrine Fund, 1988), 123–39; White et al., “Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus).”

-

C. Savage, Peregrine Falcons (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1992).

-

Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed.

-

Savage, Peregrine Falcons; Peregrine Falcons were not initially protected by the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703-712; 40 Stat. 755)—the signature federal act that today protects all North America’s native migratory birds. The species was first listed as an endangered species in 1970 (35 Federal Register 8495; June 2, 1970) under the authority of the 1969 Endangered Species Conservation Act (Public Law 91-135,835 Stat. 275). Peregrines received federal protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) on March 10, 1972 (23 U.S.T. 260; T.I.A.S. 7302), when thirty-two families of birds—including eagles, hawks, owls, and corvids—were added to a 1936 amendment of the MBTA (the Convention between the United States of America and the United Mexican States for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Game Mammals; 50 Stat. 1311; TS 912).

-

Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed. According to Ratcliffe (p. 65), “Under the war-time emergency defence regulations, the then Secretary of State for Air made on 1 July 1940 the Destruction of Peregrine Falcons Order, 1940 [No. 1164], which expired in February 1946, after the war had ended. This Order made it lawful for any properly authorised person to take or destroy Peregrines or their eggs in certain parts of Britain.” A copy of this order is provided in R. B. Treleaven, Peregrine: The Private Life of the Peregrine Falcon (Headland Publications, 1977), 147.

-

10. C. M. White, P. D. Olsen, and L. F. Kiff, “Family Falconidae (Falcons and Caracaras),” in Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2. New World Vultures to Guineafowl, eds. J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal (Lynx Edicions, 1994), 216–78.

-

Wikipedia, “Pigeon Keeping,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pigeon_keeping; A. Pettie, “Mike Tyson: Pugilist and Pigeon Fancier, Discover Channel, Review,” Telegraph, March 11, 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/8376790/Mike-Tyson-pugilist-and-pigeon -fancier-Discovery-Channel-review.html.

-

Occasional illegal persecution of peregrines and other raptors by pigeon fanciers continues to this day, as do the fanciers’ requests to relax laws protecting peregrines and other raptors. See, for example, P. Stirling-Aird, Peregrine Falcon (Firefly Books, 2012). In 2007, a group of pigeon fanciers (or “roller pigeon” enthusiasts) was charged with killing 1,000 to 2,000 raptors annually in the US. See Bruce Barcott, “Secret Agent Man: Inside the High-Stakes Life of Undercover Wildlife Agents,” Backpacker, December 2, 2021, https://www.backpacker.com/stories/adventures/danger /secret-agent-man.

-

Britain’s Protection of Birds Act (1954) included total protection for peregrines and their eggs.

-

Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed.; Savage, Peregrine Falcons.

-

J. J. Hickey, “Some Recollections about Eastern North America’s Peregrine Falcon Population Crash,” in Peregrine Falcon Populations, 9–16; Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed.; D. Ratcliffe, “Discovering the Causes of Peregrine Decline,” in Return of the Peregrine, 23–33.

-

Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed.

-

Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed.

-

Ratcliffe, The Peregrine Falcon, 2nd ed.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Oxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreThis long-lived perennial legume is used for forage and erosion control. Kudzu is edible with many medicinal uses and other applications. Pollinators of all kinds love its prodigious lavender blooms!

Read MoreMove aside, maple! We have two new syrups to add to the table. Read on for insights on tapping, selling, and eating syrup from walnut & birch trees.

Read MoreWhy is modern wheat making us sick? That’s the question posed by author Eli Rogosa in Restoring Heritage Grains. Wheat is the most widely grown crop on our planet, yet industrial breeders have transformed this ancient staff of life into a commodity of yield and profit—witness the increase in gluten intolerance and ‘wheat belly’. Modern…

Read MoreDid you ever wonder how leeks, kale, asparagus, beans, squash, and corn have ended up on our plates? Well, so did Adam Alexander, otherwise known as The Seed Detective. The following is an excerpt from the The Seed Detective by Adam Alexander. It has been adapted for the web. My Seed-Detective Mission Crammed into two…

Read More