Daylily Dangers and Delights

Got some daylilies taking over your garden? Instead of weeding them out, try eating them instead!

A common vegetable in China and Japan, the daylily is more than a pretty flower. These wild plants are easy to forage and packed with flavor that will serve as a perfect addition to seasonal recipes. Before trying them, though, there are a few factors to consider.

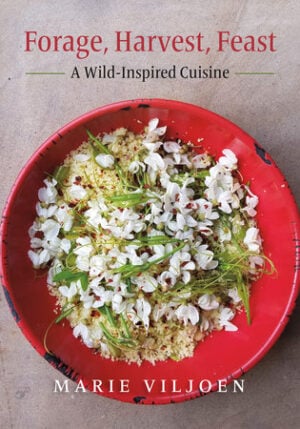

The following excerpt is from Forage, Harvest, Feast by Marie Viljoen. It has been adapted for the web.

The Dazzling Daylily

The Dazzling Daylily

Other Common Names: Ditch lily, common orange daylily, tawny daylily

Botanical Name: Hemerocallis fulva

Status: Invasive perennial in North America, vegetable in China and Japan

Where: Open ground, woodland, gardens

Season: Spring, summer, and fall

Use: Vegetable

Parts Used: Tubers, young shoots, buds, and flowers

Grow? Only if you are vigilant about their spread

Tastes Like: Green bean meets white asparagus by way of leek

Orange daylily tubers, shoots, buds, and flowers are delicious and easy to prepare and have been eaten by many thousands, if not millions, of people, for a very, very long time: They are a common food in China.

Increasingly (if you are counting in tiny increments) the shoots and buds are offered on restaurant menus, foraged and supplied by seasoned as well as newly minted professional foragers. The tender spring shoots are meltingly good when cooked slowly, like leeks. Early summer’s buds are a crisp salad ingredient with a hint of scallion breath, while the open flowers add drama to any plate. The small tubers are a very good starchy vegetable.

Is Daylily Safe to Eat?

But there is still a sense of mystery and uncertainty accompanying the edible nature of Hemerocallis fulva, and I feel it is important to illuminate the issue, at the risk of being verbose, as well as frustratingly inconclusive.

Scrupulous foraging writers will inform you that a few people experience gastric distress after eating daylilies. It is true. I know of four people who have been sickened (the symptoms are diarrhea, and sometimes vomiting) after eating the flowers of Hemerocallis fulva. One of them is wild foods author Dr. John Kallas, author of Edible Wild Plants. He and a friend became ill after eating a flower and six raw buds.

This has not happened to me, or to countless people who have eaten them with no ill effect. Understanding why it happens is a real head scratcher. It is worth putting it into a broader context. Not all toxicities are the same, and there are several factors to consider before you sit down to dinner.

Factors to Consider Before Eating Daylily

First: Not infrequently, several different plants share a common name. When talking about ingesting plants, that can lead to trouble. Some people call daylilies tiger lilies. Tiger lily is in fact Lilium lancifolium, a different genus, whose flowers are reported to be toxic, at least to cats. (Perversely, the bulbs of Lilium species are edible, when cooked. But that is another story.) So there is that. Identify your Hemerocallis fulva with certainty.

First: Not infrequently, several different plants share a common name. When talking about ingesting plants, that can lead to trouble. Some people call daylilies tiger lilies. Tiger lily is in fact Lilium lancifolium, a different genus, whose flowers are reported to be toxic, at least to cats. (Perversely, the bulbs of Lilium species are edible, when cooked. But that is another story.) So there is that. Identify your Hemerocallis fulva with certainty.

And then we get to diploids, tetraploids, and triploids. Fasten your seat belts.

Daylily Poisoning

Most documented (important distinction) daylily poisonings—human and animal—are associated with eating species daylilies (meaning not cultivars or hybrids) in Asia, where the plants are widely consumed. The toxin responsible for these poisonings appears to be hemerocallin, a neurotoxin.

The poisonings, some of which are fatal, are associated with the tubers and roots of specific species. Hemerocallis fulva is not one of them. What seems to be relevant is that the species daylilies in question are diploids. Diploids have two sets of chromosomes: one set from the egg cell and one set from the sperm in the pollen. In other words, they are fertile and make seeds.

Daylily Breeding Difficulties

Hemerocallis fulva, our common orange daylily, is a triploid. It has three sets of chromosomes and is usually infertile, as it does not set fertile seed (its invasive nature is due to its spreading rhizomes).

In daylily breeding, which is a massive industry, many of the thousands of cultivars (the word is short for “cultivated varieties,” with the name always appearing in single quotation marks) created are tetraploids—they have four sets of chromosomes.

Tetraploids are valued for ornamental reasons: larger flowers and sturdier leaves and stalks. You do not become a tetraploid by wishing it. A toxic alkaloid (not all alkaloids are bad for us) called colchicine—extracted from meadow crocus (Colchicum autumnale)—is used to induce polyploidy (more than two sets of chromosomes). It is theorized that eating daylily cultivars (bred for the horticultural trade) exposed to colchicine, rather than the good old orange ditch lily Hemerocallis fulva, may result in the distress that some foragers experience. But it is also extremely doubtful that the colchicine persists in a plant regenerated from tissue culture. These findings are not (yet, perhaps) supported by good science.

Negative Daylily Reactions

Finally, there are the bad reactions to daylilies that have been identified positively as H. fulva. Dr. Kallas says that the only pattern he has seen is that errant plants are responsible. “That is, it is not a personal food sensitivity. . . . Anyone who eats the errant plants will have symptoms. I had eaten many daylilies before . . . and have eaten many daylilies since without incident. But I have not gone back to that same patch that caused the problem.”

It is a compelling theory. Then again, I know of two foragers who have eaten raw daylily flowers and shoots from different patches in different states, experiencing gastric distress each time. Were those all errant plants? Are those people simply sensitive to daylilies? Would cooking render the plants harmless for them?

And what does this mean for us, the hungry and worried foragers?

Foraging For Daylilies

It is well worth conveying that traditional Chinese methods of preparing daylilies include soaking and blanching. Tradition carries a lot of weight. And I know of one Chinese Canadian forager (Shell Yu) with a biochemical background who scrupulously soaks buds and fresh flowers and removes their anthers and pistils. These preparation methods have been studied in China—and even if the toxin targeted in the studies may be the wrong one, perhaps the soaking leaches the plant of another.

To summarize: Daylilies have been eaten for thousands of years and can be delicious. If care is not taken in choosing your daylilies, you may have a bad time. The triploid Hemerocallis fulva is the yummy one (for most people). Avoid the diploid wild species. Avoid the horticultural cultivars. And eat daylilies (or any new food) in moderation.

To summarize: Daylilies have been eaten for thousands of years and can be delicious. If care is not taken in choosing your daylilies, you may have a bad time. The triploid Hemerocallis fulva is the yummy one (for most people). Avoid the diploid wild species. Avoid the horticultural cultivars. And eat daylilies (or any new food) in moderation.

One day, we may know more.

How to Collect and Prepare A Daylily

Tubers: Dig the tubers in early spring when the first daylily shoots are pushing above the ground. You can also dig them in early through late fall, when they have fattened up again. They will always be there waiting for you but can be more flaccid in the summer months. Wash and scrub very well, using the rough side of a sponge. They do not have to be peeled. Soak or parboil before proceeding with the recipes.

Shoots: Young tender shoots are the best to eat, and I harvest them around 3 to 8 inches in height. Their tenderness is the most important factor. Trim as you would a leek: Slit them down the middle, stopping short of the whitest end. Soak in water to dislodge any soil.

Buds and flowers: Easy, just pick.

Traditional Chinese methods advocate soaking the buds in water before eating raw or cooked. They also suggest removing the anthers and pistil from open flowers, erring on the side of caution.

Caution When Trying A Daylily

If you are trying daylilies for the first time, make sure you are have identified Hemerocallis fulva correctly. Eat a small amount. If you are surfing online for more answers, choose your sources critically, stick to scientific papers and university sites (and read between those lines, too), and absorb what experienced foragers write.

RECIPE: Braised Daylily Shoots

Serves 2 as an entrée, 4 as an appetizer

Daylily’s spring shoots have a delicate flavor reminiscent of the sweetness of slow-cooked leeks. Eat them hot or cold as an appetizer or side dish, add them to complex broths like Wild Roast Salmon with Spring Forages, layer them with thin sheets of fresh pasta, or—my favorite by far— simply lay the meltingly soft shoots over sturdy toast with a pinch of Ramp Leaf Salt, a scattering of snipped field garlic greens, and some peppery brassica flowers.

Ingredients

Ingredients

- 3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, plus extra

- 8 ounces (227 g) daylily shoots (12–20, depending on size), trimmed and well washed

- 1/4 cup (60 ml) water

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- Black pepper

- 2 teaspoons lemon juice

- 4 slices sturdy bread

- Pinch of Ramp Leaf Salt

- Field garlic greens (optional)

- Arugula or mustard flowers (optional)

Procedure

- Heat the oil over medium heat in a skillet. Add the shoots in a single later.

- Pour in the water and season with the salt and pepper.

- Bring the liquid to a boil, then reduce the heat to low and braise gently for 20 minutes, covered.

- Add the lemon juice, turn the shoots over, and cook another 15 minutes.

- For the last 5 minutes, increase the heat to medium-high to cook off any remaining liquid.

- Toast the bread and drizzle it with some extra olive oil.

- Lay the daylily shoots on top, season lightly with the Ramp Leaf Salt, and scatter the field garlic greens and flowers across the top, if using.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Searching for a new way to utilize seasonings? Look no further than mint salt! This game-changer is bound to mix up the way you season meals in the future.

Read MoreWhen you save seeds, you become a plant breeder! Take control of your seeds and grow the best traditional and regional varieties and even develop your own.

Read MoreFire Cider is great for stimulating digestion and warming you up from the inside out, no matter the season. This beverage can be prepared in water or tea as desired.

Read MoreSave seeds, save the future! Embracing the tradition of saving seeds is a powerful practice for both home gardeners and seasoned horticulturists alike. Take control of your garden’s destiny – start saving seeds today!

Read MoreReady to shake up your fermentation game? Try making Kvass, the ultimate beginner-friendly recipe! This nourishing beverage calls for just a few simple ingredients and only takes a couple of days to ferment. It’s easy, delicious & perfect for beginners.

Read More

The Dazzling Daylily

The Dazzling Daylily Ingredients

Ingredients