Starting & Growing A Flower Farm: What to Consider

Want to start a flower farm? Most of your decisions when starting and growing a farm are interdependent, so it can be hard to know where to start.

The following is an excerpt from Flower Farming for Profit by Lennie Larkin. It has been adapted for the web.

Featured photo by Molly DeCoudreaux.

Take Stock of Your Resources

Before planning what crops to grow, where to sell them, and how to build systems on your farm, you first need to take stock of the resources you have at hand and the ones you’ll need.

So, let’s start with the basics: your knowledge and experience with farming, a broad view of flower farm finances, and an assessment of the resources and growing space you have to work with.

Knowledge and Experience

On-the-job training is invaluable, nowhere more so than in farming.

I don’t know one grower who wouldn’t recommend learning on someone else’s dime before starting your own business.

You simply can’t learn efficient farm operations on your own in one lifetime.

Whether it’s transplanting, picking flowers, or weeding, farming is full of tasks that can look drastically different when performed by a novice versus an expert.

You could spend one hour planting twenty plants as a novice, whereas an expert farmer could use that same hour to plant thousands of seedlings. And to think that farming is written off as “unskilled labor”!

Because many flower crops have a short growth window, you only get to experience growing them for a brief period each season.

For example, I’ll only go through the process of planting dahlias about thirty times in my life, so I don’t have time to waste the first few years learning by trial and error.

Getting A Leg Up: Knowing Other Farmers

For this reason, working under the tutelage of an experienced farmer can give you a leg up.

There are certainly people out there who just jump right in, but I’d suspect they have the money, time, or both, that most don’t have at our disposal when we start out flower farming. No matter your experience, you’ll get further if you connect with other farmers and mentors early in the game.

Farm Infrastructure

Some certainly get away without these for the first few years and some for far longer, but we’re talking about long-term, efficient farming and sticking to the rule rather than the exception.

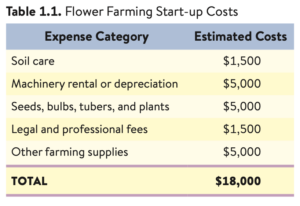

Table 1.1 gives a good sense of the typical start-up costs for a 1-acre flower farm.

High- and Low-Maintenance Crops

Some crops need little in the way of specialized equipment or infrastructure. Zinnias are best grown out in the open field and don’t need (and in fact don’t appreciate) a cooler.

Tulips and peonies, on the other hand, absolutely need to be stored in a cooler because they bloom all at once. Sweet peas won’t have much of a vase life without a cooler, and most people don’t bother to grow dinnerplate dahlias without the use of a hoop house.

Growing sunfloers in large quantities means transporting their bulky stems from the field to the processing area, so you’ll need at least a cart if not a farm truck and roads that lead right up to the field’s edge.

As you consider which crops to grow, it’s imperative to consider what equipment and infrastructure a crop will need and what you may need to purchase or build.

Land Considerations

You need to consider how much land you have avail- able to work with at the outset. Your farm will likely grow whether you plan for it or not, but defining your resources at the start will allow you to better design your business.

If you’re on an urban lot and limited to the 1/4 acre behind your house, you’re in a different situation than the farmer who lives on 100 wide-open acres in the middle of nowhere. Most of us are some- where in the middle.

And while you can possibly buy or lease more land, clear more forest, or move, it’s best to have a general plan for the first three or so years in business in your current location. When in doubt, plan to cultivate less space than you think you’ll need.

How Much Land Do You Need for A Flower Farm?

The smallest amount of land you might need to start a flower farm—if you’re selling direct to consumer and therefore achieving a higher price point than wholesale—is about 1/4 acre, 1/2 if you’re really trying to run a business that will sustain you throughout your career.

This amount of space can produce more flowers than you can likely imagine, and getting them sold is a whole other job that will often demand more hours than exist in a day. A few flower beds go a long way.

Do You Need Your Own Land For A Flower Farm?

You don’t need to own your land to run a flower farm, but it sure is helpful.

As a perennial tenant who has farmed on five different leased fields over 10 years, I can tell you that you can make it work but also that I wouldn’t recommend doing it without a solid, long- term lease of contiguous acres.

I’m sure we’ve all read about flower farmers making a go of it in their own or others’ backyards, in urban lots, or on patches of leased land around town, but I would challenge you to find more than a few of these who are still operating in earnest after 5 or 10 years.

There’s a big difference between just making something work and finding a sustainable solution that will suit your business and personal needs in the long run.

Beginning On Leased Land

Many flower farmers begin on leased land, build a financially sustainable business, and then purchase land once they can afford it and know what type and size of plot they need for their operation.

This is usually only possible if you already have savings from elsewhere; it’s a lot to ask of a small farm to raise enough money for a land purchase. This is my exact situation for my own operation, B-Side Farm.

I farmed for 10years and learned exactly what I needed, saving money all the while from teaching and garden design in addition to farming. I finally bought a farm of my own in 2022.

I had to move from California to Oregon to afford the purchase, essentially starting the business over, but that’s a story for another book.

Defining “Acreage under Cultivation”

Large pathways allow for easy visitor access at Haystack Farm in Sonoma, CA. Photo by Molly DeCoudreaux

When talking about farm size, an acre is not an acre is not an acre. Oh, semantics! There’s no standard way to define what constitutes the size of your farm.

A farmer who owns 5 acres and has a few small fields scattered throughout may well tell you that they have a 5-acre farm.

Another farmer who owns a total of 1 acre and fills it with crops from one end to the other may well have the same number of plants in the ground as the first farmer.

Typically, what a farmer calls their growing space will include the combined total of their fields, excluding major roads, tree lines, and empty space but including the pathways between the actual planting beds.

A clear way of defining your space may be to say, “We have 5 acres but grow on just about 1 of them.”

How Big Should Your Pathways Be?

Then we have the question of pathway size. For farms such as mine that were born of bio-intensive methods, we go by the slogan “You can’t make money in the pathways.”

The narrowest I’ve gone is 12 inches, but 18 inches feels about right as it doesn’t slow down movement between beds.

But on pick- your-own farms, wheelchair-accessible farms, or farms that choose to rely on riding mowers to manage the grass between their permanent beds, pathways may be much wider.

With such a system, you can easily fill an acre with flowers, or so it would seem, but you’re really growing more grass than flowers. I do fantasize about this type of farm, wandering barefoot between the beds. One day.

Flower Farm Plant Spacing

And finally, plant spacing in cut flower production means throwing all assumptions about space out the window.

Some crops, like peonies and roses, need a lot of space (think winter squash in the vegetable gar- den). It’s not worth cramming them in, because they’ll hardly produce a viable crop if you do so. An acre of roses planted at 1 row per bed, plants spaced 2 to 3 feet apart, will contain only about 2,400 plants.

An acre of something like lisianthus, planted at 6 rows per bed and 4 inches apart, can contain 144,000 plants. An acre of roses hardly sounds crazy, whereas an acre of lisianthus is hard to even imagine and would be a monumental challenge to sell.

Keep an open mind as you begin to think about how much land you might need to cultivate to build your business.

Your Finances

We all have different financial needs and expect different financial returns from our farms.

Some of us need to bring in enough income to cover our own living expenses, others are supporting whole families with their farm, and others are satisfied if sales just cover the cost of a flower-growing hobby.

Some plan to keep their day job forever, some see farming as a side hustle as they transition out of a career, and those few who have some prior farming experience may jump right in full time from the start.

There’s been tremendous growth in our industry on all levels over the past 20 years.

An Increase In Flower Farmers

Flower farming is an understandable obsession, and there’s room for all of us. But the increase in the number of both hobby and professional businesses has certainly muddied the landscape.

The rise of social media and influencer culture makes it difficult to tease apart the good information from the bad, the farm experts from those who have more marketing savvy than applicable wisdom.

Without knowing the context behind the farms that have made their way into the public eye, it’s hard to get a sense of the true financial picture of flower farming.

Flower Farm Salaries

People often ask me if they can truly expect to leave a full-time job and replace that salary by farming.

My answer is never straightforward, but I do make it clear that replacing an average US salary of about $60,000 or so is possible if you have some experience, some money to invest, and can put in 5-plus years of focused work.

If all of these conditions don’t line up for you (and they often don’t), you might be looking at making half that amount for a number of years.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Want to get started with silvopasture? The first step is figuring out which type of livestock works best for your ecosystem.

Read MoreExtend Your Growing Season with a Cold Frame! Plant earlier in spring AND grow later into fall. Build your own cold frame and enjoy a longer harvest season! Ready to grow more, longer?

Read MoreGrowing year-round is a challenge, but it’s not impossible. Follow these growing tips, and you’ll be well on your way to growing year-round!

Read MoreDoes the cold weather have you dreaming about fresh greens and colorful salad? Tired of waiting for spring to enjoy fresh greens? Grow and harvest sprouts indoors to make those dreams a reality!

Read More