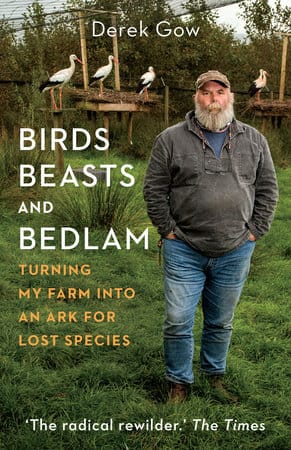

Turning My Farm into an Ark for Lost Species: Not a Lark or a Lizard Lived There

Birds, Beasts and Bedlam recounts the adventures of farmer-turned-rewilder Derek Gow, who is saving Britain’s much-loved but dangerously threatened species, from the water vole to beaver, tree frog to glow worm and returned honking skeins of graylag geese to the land and water that was once theirs.

The following is an excerpt from Birds, Beasts and Bedlam: Turning My Farm into an Ark for Lost Species by Derek Gow. It has been adapted for the web.

The snake-headed clusters of the greylag geese look like hydras in the long grass

Orange billed and dark eyed with light surrounding rims, they turn together when sitting to watch you pass at a comfortable distance. Come too close and they will fly, exposing their broad white tails and orange feet. Although the black-necked Canadas with their white face flashings, which followed them to us, have a light tail pattern too, theirs is banded with black at its tip and top where it meets their main body.

They are a darker goose overall, more ash brown in colour with black legs and bills. Occasionally an oddity appears, an escape from elsewhere. Dapper barnacles like small city clerks with bowlers, waistcoats and plumpish pale cheeks; exotic, tawny Egyptian geese, sand fawn with Cleopatra’s eyes and bottle-green wing tips or a snow goose frosted crystal. No shooting occurs on our land and all know they are safe.

The greylags were the first of my reintroductions

In their first spring season, the females disappeared and their aggressively honking mates’ necks extended and patrolled the edges of the dense rush beds into which they had vanished. Weeks later, they emerged with broods of tiny yellow, fluffy coated, black-beaked goslings. When these assumed their adult feathering in the late summer of the year, they eventually flew free.

That was nearly fifteen years ago and flocks of hundreds are now quite common

Some have extended out onto reservoirs nearby. In the summer they prefer the mown or grazed grass of my neighbours to the tall swards or pig- ploughed environments of my own farm. In the winter, as the grass dies back, they land in their flocks to flatten its structure irregardless.

In the mornings and evenings, whether inside or out, their V-shaped skeins flying over my cottage to the west are unavoidably vocal. No one has complained much yet but when nature starts to burgeon it overspills. Together with the water voles, polecats and beavers descended from those that escaped, the geese now are unrestricted in their freedom to live and to die.

We have been visited twice in 2021 by individual white-tailed eagles from the release on the Isle of Wight. Secure as they are in their large flocks dotted and grazing in the green, the geese have had no reason yet to look upwards for danger. One day soon the eagles will find them. Their time of ease is ebbing.

__________

In 2003 when I moved to Devon my hopes were low.

Deflated in aspiration by what it seemed had become an eternal life game of snakes and ladders, and with my desire to create a breeding centre for endangered British wildlife, which I was convinced was essential, in the doldrums, I purchased a small L-shaped house in a tiny plot of land.

The ranks of water vole pens in the small field that came with the property absorbed little time on a daily basis and, having been badly built by its former farming owner who was a bodger of the broadest sort, the smallholding offered diverting issues galore to absorb my attention.

Sorting the drains that tracked water back into the dwelling, infilling huge cracks that were present in its outbuildings and removing a gigantic mound growing bright green outside the door of a large barn, which turned out to be the grave site of nearly ten thousand dead rabbits that had died in the course of a week when a former owner’s breeding population of New Zealand whites contracted viral haemorrhagic disease.

While it was diverting in the summer that followed my departure from Kent to tiddle with these humdrum concerns, a decade of developing purpose near completely spirited away left an uneasy undertone. When Paul Ramsey, my old Scottish beaver pal, called me one day to ask if I had a building which could be converted to quarantine beavers and other friends confirmed that they would like me to import some for them as well, I phoned the Bavarians and began again.

Further opportunities to do things that I truly enjoyed then followed in quick order. More offers appeared to guide groups overseas and in doing so reignite my lapsed child- hood passion for investigating meadows, pools or rock clefts to unearth the creatures they contained. Bright blue slugs, it transpired, were a speciality of the Carpathians. Grey-headed rock thrushes with bright tangerine breasts were abundant in the Pyrenees.

Emerald-green tree frogs in Croatian vehicle ruts. Montandon’s many-spotted newt in the same environments on the Polish border with the Ukraine. At Čigoč on the Sava River I saw a thatched village of wooden houses and barns where a huge colony of white storks, which had built their great stick nests on roofs, were near utterly ignored by the peasant farmers that lived and worked beneath them.

Work went well and more commercial contracts created an income stream, which was stable rather than affluent. Before my mother died leaving a small legacy, I never contemplated agriculture as a realistic profession – the capital costs were just too high – but in 2006 when the old farmer decided to sell his farm at Upcott Grange just next to my cottage, I used her money in part to purchase 120 acres of wet dairy land.

The farm had a broken-down steading with old cattle stalls and neck chains, a larger shed for young stock, which flooded every time it rained, sheep-handling facilities in a state of near ruin and an infrastructure which was otherwise pretty much entirely decrepit.

I acquired small flocks of sheep and a herd of blood-red short-horned cattle not because I really wanted to farm but rather to avoid the dissolution of the land, fences, gates and infrastructure that commonly follows when its owner rents its use to another. Casual tenants have no care, they just want a quick return for their cash spent and swiftly or slowly all degrades.

I never thought at the beginning about using the land for nature.

As my neighbours were all farming and blagging about the success of their undertakings, I just believed that as everyone else who was doing so was obviously – despite their raggedness – making a mint that I, too, might as well invest in proper infrastructure and in doing so develop some additional income. I installed new tracks to carry tractors and vehicles out into the fields.

More renovation. Further knocking down, building, fencing and repurposing for a new future. By the time I finished, the sheep could trip-trap wherever they so wished without getting their dainty hooves damp.

Other projects came along from old contacts. I erected a few larger wild animal pens for film and photography work and in 2014 assisted with the production of a series commissioned by BBC2 to explain the lifestyles of bur- rowing animals.

Once again, I was creating intricate artificial worlds for the wild creatures which live all around us or, in the case of the subterranean species, quite literally under our feet. Underground is dark and moist. This is an inescapable reality. Although the producers of what became The Burrowers tried to capture genuine footage of life down under by sending intrepid ferrets into the dark with small infrared cameras strapped to backpack harnesses, it was all a bit of a flop.

Their expensive kit was scraped off underground, misted up swiftly or, most gallingly of all for those not used to ferret exploration, was underused by their transporters who, after a short period of snuffling, were inclined to yawn and fall asleep. As high-definition, full-colour TV was required, artificial film sets were the only way forward. A large underground warren made from yellow sand, with tunnels and chambers for the rabbits.

A dark woodland loam-feel with large sleeping quarters for the badgers. Tight tunnels with chambers of strange shapes based on the sort of features we had allowed captive water voles to create in trays of damp soil in their breeding pens. Tiny weeny straight ones with small nesting areas were made for the moles. Whole wooden buildings were erected to house these delicate film environments.

Tunnels and runs made from more wood and wire mesh led the rabbits and badgers from their outdoor paddocks into the areas where we wished to film. As external footage of the water voles was also an essential prerequisite, a river tank setting with fern-studded bankings, lush wetland plants and a small stream was created for their use.

It’s never that simple.

The badgers, content to explore their film set without issue decided in the end to dig a burrow in their outside pen, live there instead and use the indoor area we had skilfully wrought to resemble a series of chambers clasped by the great curling roots of an oak as a toilet. The wild rabbits, difficult and delicate, fought whenever more than a pair of opposite sexes were introduced and were replaced in the end by lookalike domestics which were much more sedate.

The male water vole was terrified of his grim, aggressive female who so dominated both him and their offspring that when they reached the age of 14 days they all wanted to leave home. The mole whose eyes were too small to show a satisfied expression trashed with its gouging forefeet every set we introduced it to with glee.

Even when we thought all was simple and our control near complete, their ability to defeat our intent was formidable.

Derek Gow is a farmer and nature conservationist who has played a significant role in the reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver, the water vole, and the white stork in England. His conservation work has been featured in The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The Guardian, BBC, The London Times, and numerous other national and international media. He lives with his children on a 300-acre farm on the Devon/Cornwall border which he is in the process of rewilding.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Have you ever wondered why fig trees are considered a symbol of abundance and fertility across cultures? What exactly makes these trees so special?

Read MoreSeeds strengthen our connections to what we grow and eat; they are intrinsic to our identity and our future. I cherish seed as a common resource that all the world should be able to access freely.

Read MoreCultivating mushrooms on various substrates has many benefits — from composting, mycoremediation, and creating value-added consumer goods. It helps reduces waste and helps the environment!

Read MorePlanting cover crops is a key step in transforming dirt into soil! The benefit list is long but they need to be selected with a purpose.

Read MoreWith more than 80 percent of the US population now residing in urban areas food forests help provide a local food source. And they also serve as perfect platforms for community-building.

Read More