Ditch the Pots, Use Soil Blocks!

What’s a cheaper, easier, and surprisingly more efficient way to start your seedlings? Soil blocks!

If you’ve never used them before, read on to find out how soil blocks work, how you make them, and what advantages they offer over traditional pots and trays.

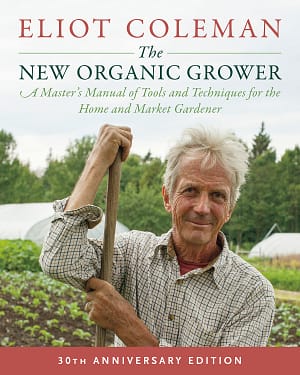

The following is an excerpt from The New Organic Grower by Eliot Coleman. It has been adapted for the web.

How Soil Blocks Work

A soil block is pretty much what the name implies—a block made out of lightly compressed potting soil. It serves as both the container and the growing medium for a transplant seedling. The blocks are composed entirely of potting soil and have no walls as such. Because they are pressed out by a form rather than filled into a form, air spaces provide the walls. Instead of the roots circling as they do upon reaching the wall of a container, they fill the block to the edges and wait. The air spaces between the blocks and the slight wall glazing caused by the block form keep the roots from growing from one block to another. The edge roots remain poised for rapid outward growth. When transplanted to the field, the seedling quickly becomes established. If the plants are kept too long in the blocks, however, the roots do extend into neighboring blocks, so the plants should be transplanted before this happens.

Despite being no more than a cube of growing medium, a soil block is not fragile. When first made, it is bound together by the fibrous nature of the moist ingredients. Once seeded, the roots of the young plant quickly fill the block and ensure its stability even when handled roughly. Soil blocks are the answer for a farm-produced seedling system that costs no more than the “soil” of which it is composed.

Advantages

The best thing about the soil-block system is that everything that can be done in small pots, “paks,” trays, or plugs can be done in blocks without the expense and bother of a container. Blocks can be made to accommodate any need. The block may have a small depression on the top in which a seed is planted, but blocks can also be made with a deep center hole in which to root cuttings. They can also be made with a large hole in which to transplant seedlings. Or they can be made with a hole precisely the size of a smaller block, so seedlings started in a germination chamber in small blocks can be quickly transplanted onto larger blocks.

Blocks provide the modular advantages of plug trays without the problems and expense of a plug system. Blocks free the grower from the mountains of plastic containers that have become so ubiquitous of late in horticultural operations. European growers sell bedding plants in blocks to customers, who transport them in their own containers. There is no plastic pot expense to the grower, the customer, or the environment. In short, soil blocks constitute the best system I have yet found for growing seedlings.

The Soil-Block Maker

The key to this system is the tool for making soil blocks—the soil-block maker or “blocker.” Basically, it is an ejection mold that forms self-contained cubes out of a growing medium. Both hand and machine models are available. For small-scale production, hand-operated models are perfectly adequate. Motorized block-making machines have a capacity of over 10,000 blocks per hour. But they are way overscaled for a 5-acre vegetable farm.

There are two features to understand about the blocker in order to appreciate the versatility of soil blocks: the size of the block form and the size and shape of the center pin.

The Form

Forms are available to make ¾-inch blocks (the mini-blocker), 1½-inch blocks, 2-inch blocks, 3-inch blocks, and 4-inch blocks (the maxi-blocker). The block shape is cubic rather than tapered. Horticultural researchers have found a cubic shape to be superior to the tapered-plug shape for the root growth of seedlings.

Two factors influence choice of block size—the type of plant and the length of the intended growing period prior to transplanting. For example, a larger block would be used for early sowings or where planting outside is likely to be delayed. A smaller block would suffice for short-duration propagation in summer and fall. The mini-block is used only as a germination block for starting seedlings.

Obviously, the smaller the block, the less potting mix and greenhouse space is required (a 1½-inch block contains less than half the volume of a 2-inch block). But, in choosing between block sizes, the larger of the two is usually the safer choice. Of course, if a smaller size block is used, the plants can always be held for a shorter time. Or, as is common in European commercial blocking operations, the nutrient requirements of plants in blocks too small to maintain them can be supplemented with soluble nutrients. The need for such supplementary fertilization is an absolute requirement in plug-type systems, because each cell contains so much less soil than a block. The popular upside-down pyramid shape, for example, contains only one-third the soil volume of a cubic block of the same top dimension.

My preference is always for the larger block, first because I believe it is false economy to stint on the care of young plants. Their vigorous early growth is the foundation for later productivity. Second, I prefer not to rely on soluble feeding when the total nutrient package can be enclosed in the block from the start. All that is necessary when using the right size block and soil mix is to water the seedlings.

Another factor justifying any extra volume of growing medium is the addition of organic matter to the soil. If lettuce is grown in 2-inch blocks and set out at a spacing of 12 by 12 inches, the amount of organic material in the blocks is the equivalent of applying 5 tons of compost per acre! Since peat is more than twice as valuable as manure for increasing long-term organic matter in the soil, the blocks are actually worth double their weight in manure. Where succession crops are grown, the soil-improving material added from transplanting alone can be substantial.

The Pin

The pin is the object mounted in the center of the top press-form plate. The standard seed pin is a small button that makes an indentation for the seed in the top of the soil block. This pin is suitable for crops with seeds the size of lettuce, cabbage, onion, or tomato. Other pin types are dowel- or cube-shaped. I use the cubic pin for melon, squash, corn, peas, beans, and any other seeds of those dimensions. A long dowel pin is used to make a deeper hole into which cuttings can be inserted. Cubic pins are also used so a seedling in a smaller block can be potted on to a larger block; the pin makes a cubic hole in the top of the block into which the smaller block is placed. The different types of pins are easily interchangeable.

Blocking Systems

Mini-blocks are effective because they can be handled as soon as you want to pot on the seedlings. The oft-repeated admonition to wait until the first true leaves appear before transplanting is wrong. Specific investigations by W.J.C. Lawrence, one of the early potting-soil researchers, have shown that the sooner young seedlings are potted on, the better is their eventual growth.

The 1½-inch block is used for short-duration transplants of standard crops (lettuce, brassicas) and as the seed block for cucumbers, melons, and artichokes by using the large seed pin. When fitted with a long dowel pin it makes an excellent block for rooting cuttings.

The 2-inch block is the standard for longer-duration transplants. When fitted with the ¾-inch cubic pin, it is used for germinating bean, pea, corn, or squash seeds and for the initial potting on of crops started in mini-blocks.

The 3-inch block fitted with a ¾-inch cubic pin offers the option to germinate many different field crops (squash, corn, cucumber, melon) when greenhouse space is not critical. It is also an ideal size for potting on asparagus seedlings started in mini-blocks.

The 4-inch block fitted with a 1½- or 2-inch cubic pin is the final home of artichoke, eggplant, pepper, and tomato seedlings. Because of its cubic shape, it has the same soil volume as a 6-inch pot and can grow exceptional plants of these crops to their five- to eight-week field transplant age.

Other Pin Options

In addition to the pins supplied with the blocker, the grower can make a pin of any desired size or shape. Most hard materials (wood, metal, or plastic) are suitable, as long as the pins have a smooth surface. Plug trays can be used as molds and filled with quick-hardening water putty to make many different sizes of pins that allow the integration of the plug and block systems.

Blocking Mixes

When transplants are grown, whether in blocks or pots, their rooting area is limited. Therefore the soil in which they grow must be specially formulated to compensate for these restricted conditions. For soil blocks, this special growing medium is a blocking mix. The composition of a blocking mix differs from an ordinary potting soil because of the unique requirements of block-making. A blocking mix needs an extra fibrous material to withstand being watered to a paste consistency and then formed into blocks. Unmodified garden soil treated this way would become hard and impenetrable. A blocking mix also needs good water-holding ability, because the blocks are not enclosed by a nonporous container. The bulk ingredients for blocking mixes are peat, sand, soil, and compost. Store-bought mixes can also work, but most will contain chemical additives not allowed by many organic certification programs. If you can find a commercial peat-pearlite mix with no additives, you can supplement it with the soil, compost, and extra ingredients described below.

In the past few years commercial, preformulated organic mixes with reasonably goof growth potential have begun to appear on the market. However, shipping costs can be expensive if you live far away from the supplier. To be honest, I have yet to find any of these products that will grow as nice seedlings as my own housemade mixes.

Peat

Peat is a partly decayed, moisture-absorbing plant residue found in bogs and swamps. It provides fiber and extra organic matter in a mix. All peats are not created equal, however, and quality can vary greatly. I recommend using the premium grade. Poor-quality peat contains a lot of sticks and is very dusty. The better-quality peats have more fiber and structure. Keep asking and searching your local garden suppliers until you can find good-quality peat moss. Very often a large greenhouse operation that makes its own mix will have access to a good product. The peat gives “body” to a block.

Sand

Sand or some similar granular substance is useful to “open up” the mix and provide more air porosity. A coarse sand with particles having a 1/8 to 1/16 inch diameter is the most effective. I prefer not to use vermiculite, as many commercial mixes do, because it is too light and tends to be crushed in the block-making process. If I want a lighter-weight mix I replace the sand with coarse perlite. Whatever the coarse product involved, adequate aeration is key to successful plant growth in any medium.

Compost and Soil

Although most modern mediums no longer include any real soil, I have found both soil and compost to be important for plant growth in a mix. Together they replace the “loam” of the successful old-time potting mixtures. In combination with the other ingredients, they provide stable, sustained-release nutrition to the plants. I suspect the most valuable contribution of the soil may be to moderate any excess nutrients in the compost, thus giving more consistent results. Whatever the reason, with soil and compost included there is no need for supplemental feeding.

Compost is the most important ingredient. It is best taken from two-year-old heaps that are fine in texture and well decomposed. The compost heap must be carefully prepared for future use in potting soil. I use no animal manure in the potting-mix compost. I construct the heap with 2- to 6-inch layer of mixed garden waste (e.g. outer leaves, pea vines, weeds) covered with a sprinkling of topsoil and 2 to 3 inches of straw sprinkled with montmorillionite clay. The sequence is repeated until the heap is complete. The heap should be turned once the temperature rises and begins to decline so as to stimulate further decomposition.

There are no worms involved in our composting except those naturally present, which is usually a considerable number. (I have purchased commercial worm composts [castings] as a trial ingredient, and they did make an adequate substitute for our compost.) Both during the breakdown and afterwards the heap should be covered with a landscape fabric. I strongly suggest letting the compost sit for an additional year (so that it is one and a half to two years old before use); the resulting compost is well worth the trouble. The better the compost ingredient, the better the growth of the plants will be. The exceptional quality of the seedlings grown in this mix is reason enough to take special care when making a compost. Compost for blocking mixes must be stockpiled the fall before and stored where it won’t freeze. Its value as a mix ingredient seems to be enhanced by mellowing in storage over the winter.

Soil refers to a fertile garden soil that is also stockpiled ahead of time. I collect it in the fall from land off which onions have just been harvested. I have found that seedlings (onions included) seem to grow best when the soil in the blocking mix has grown onions. I suspect there is some biological effect at work here, since crop-rotation studies have found onion (and leeks) to be highly beneficial preceding crops in a vegetable rotation. The soil and compost should be sifted through a ½-inch mesh screen to remove sticks, stones, and lumps. The compost and peat for the extra-fine mix used either for mini-block or for the propagation of tiny flower seeds are sifted through a ¼-inch mesh.

Extra Ingredients

Lime, blood meal, colloidal phosphate, and greensand are added in smaller quantities.

Lime. Ground limestone is added to adjust the pH of the blocking mix. The quantity of lime is determined by the amount of peat, the most acidic ingredient. The pH of compost or garden soil should not need modification. My experience, as well as recent research results, has led me to aim for a growing medium pH between 6 and 6.5 for all the major transplant crops. Those growers using different peats in the mix may want to run a few pH tests to be certain. However, the quantity of lime given in the formula below works for the different peats that I have encountered.

Blood Meal. I find this to be the most consistently dependable slow-release source of nitrogen for growing mediums. English gardening books often refer to hoof-and-horn meal, which is similar. I have also used crab-shell meal with great success. Recent independent research confirms my experience and suggests that cottonseed meal and dried whey sludge also work well.

Colloidal Phosphate. A clay material associated with phosphate rock deposits and containing 22 percent P2O5. The finer the particles the better.

Greensand (Glauconite). Greensand contains some potassium but is used here principally as a broad-spectrum source of micronutrients. A dried seaweed product like kelp meal can serve the same purpose, but I have achieved more consistent results with greensand.

The last three supplementary ingredients—blood meal, colloidal phosphate and greensand—when mixed together in equal parts are referred to as the “base fertilizer.”

Blocking Mix Recipe

A standard 10-quart bucket is the unit of measurement for the bulk ingredients. A standard cup measure is used for the supplementary ingredients. This recipe makes approximately 2 bushels of mix. Follow the steps in the order given.

- 3 buckets brown peat

- ½ cup lime. Mix.

- 2 buckets coarse sand or perlite

- 3 cups base fertilizer. Mix.

- 1 bucket soil

- 2 buckets compost

Mix all ingredients together thoroughly.

The lime is combined with the peat because that is the most acidic ingredient. Then the sand or perlite is added. The base fertilizer is mixed in next. By incorporating the dry supplemental ingredients with the peat in this manner, they will be distributed as uniformly as possible throughout the medium. Next add the soil and compost, and mix completely a final time.

Mini-Block Recipe

A different blend is used for germinating seeds in mini-blocks. Seeds germinate better in a “low-octant” mix, without any blood meal added. The peat and compost are finely screened through a ¼ inch mesh before adding them to the mix.

- 4 gallons brown peat

- 1 cup colloidal phosphate

- 1 cup greensand (If greensand is unavailable,

- leave it out. Do not substitute a dried seaweed product in this mix.)

- 1 gallon compost (well decomposed)

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Nothing says “spring” like a fresh, foraged meal! Savor the flavors of the season with this Milkweed Bud Pizza recipe.

Read MoreOxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreSo you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start? Learn how to break down the options of harvesting tools!

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read More