What You Didn’t Learn About “Leaves of Grass” in School

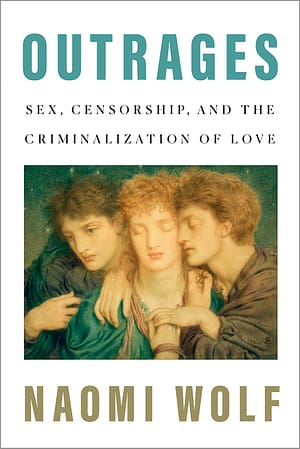

In her book Outrages, Naomi Wolf shows how legal persecutions of writers, and of men who loved men affected Symonds and his contemporaries, including Christina and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Walter Pater, and the painter Simeon Solomon. All the while, Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass was illicitly crossing the Atlantic and finding its way into the hands of readers who reveled in the American poet’s celebration of freedom, democracy, and unfettered love.

Inspired by Whitman, and despite terrible dangers he faced in doing so, Symonds kept trying, stubbornly, to find a way to express his message—that love and sex between men were not “morbid” and deviant, but natural and even ennobling.

The following is an excerpt from Outrages by Naomi Wolf. It has been adapted for the web.

(Carving on exterior of Magdalen College; Photo Credits: Jon Bower Oxford / Alamy Stock Photo)

The History of Leaves of Grass

In his quest for freedom and equality for men who loved men, Symonds had help from an unlikely source. Leaves of Grass—a volume of poems published in 1855 by the American poet Walt Whitman—would be the catalyst of a lifetime for Symonds. This collection, in an utterly original voice, robustly celebrates the self and its euphoric relationship to the natural world and to other men and women.

It sent transformational ripples through British and American subcultures. It would affect groups of London bohemians, Boston Transcendentalists, artists, writers, feminists, Socialists, Utopians, reformers, and revolutionaries, who would in turn create new ways of seeing human sexuality, social equality, and love itself, and who would use that vision in turn to build new institutions.

Whitman lines from Leaves of Grass carved into New York City’s AIDS memorial, 2016; Photo Credits: Richard Levine / Alamy Stock Photo

There would eventually be seven to ten authorized editions of the book, depending, as scholars point out, on what you count as an edition. There would be the real Leaves of Grass; the forged Leaves of Grass; the pirated Leaves of Grass; the bowdlerized, legal Leaves of Grass; and the smuggled, uncensored, illegal Leaves of Grass.

There would be the Leaves of Grass that was read in private groups of workingmen in northern Britain, who felt it spoke especially to them, and the Leaves of Grass that early feminists read in London, New York City, and Philadelphia, who believed that it spoke uniquely to them as well.

After reading Leaves of Grass as a young man, Symonds would spend the rest of his life trying to respond to the book’s provocative themes.

Physically fragile, status-conscious, fearful of social rejection, Symonds recognized a temperamental opposite in Whitman. The older poet was fearless, physically robust, all-embracing, stubborn in his convictions, unashamedly prophetic, and perfectly ready to upset everybody.

Symonds never met Whitman in person, but the two maintained an epistolary friendship across the Atlantic, at a time when letters were transported on six-week journeys by ships under sail. The Englishman’s sometimes overbearing literary courtship of Whitman would span more than two decades.

Comforted and provoked by this friendship, Symonds gradually became less and less guarded. At the very end of his life, he finally stopped trying to express his feelings in veiled ways and burst out at last into straightforward advocacy. His foundational essay, A Problem in Modern Ethics, circulated secretly before his death, declared outright that love between men was natural, and that it was good.

At the end of his life, he collaborated on the sexological treatise Sexual Inversion, which would introduce the concept of homosexuality as an identity on a natural spectrum of sexual identities, as we understand it today. That argument bears with it an implicit claim for equal treatment of men who love men. A Problem in Modern Ethics could well have been the first gay rights manifesto in English.

Given the significance in LGBTQ+ history of John Addington Symonds’s story, I asked many members of that community to read this book in manuscript. Based on their responses, I wish to share some notes.

Language about sexuality and gender is always evolving. I did my best, when describing the past, to use language that was accurate for the time, while still being alert to present-day usage.

My research found a deep connection between the origins of the feminist movement in the West, the modern (re-)invention of Western homophobia, and the start of the Western gay rights movement; this emboldened me to a degree to undertake this task.

John Addington Symonds, paterfamilias; Photo Credits: University of Bristol Library, Special Collections (DM375/1)

Nonetheless I had a sense of humility, not being identified as a member of the LGBTQ+ community, in undertaking to tell this story. I was advised by my LGBTQ+ readers of the importance of the author’s transparency.

So I am sharing that while I do not identify as a member of this community, I am aware of the responsibilities of an ally. This research material came my way; I was moved to do my utmost to shine a light on it.

By the time of Symonds’s death, in 1893, a new generation of men such as Oscar Wilde were less indirectly signaling in their work what we would call gay themes and were no longer so willing to inhabit what we today call “the closet.”

Many commentators describe the movement for gay rights as originating with Wilde and the trials of 1895 that brought down the playwright, sentencing him to two years’ hard labor in prison.

But a generation before Wilde, a small group of “sexual dissidents,” influenced by Symonds and his loving friend and sometime adversary Walt Whitman, struggled at great personal risk and in the face of extraordinary oppression to advocate for these freedoms.1

- Jonathan Dollimore coined this phrase in his 1991 book Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Why is modern wheat making us sick? That’s the question posed by author Eli Rogosa in Restoring Heritage Grains. Wheat is the most widely grown crop on our planet, yet industrial breeders have transformed this ancient staff of life into a commodity of yield and profit—witness the increase in gluten intolerance and ‘wheat belly’. Modern…

Read MoreAddressing the pressing issues affecting everyday Americans is essential—and one of our nation’s most profound challenges is the devastating impact of mass layoffs. Layoffs upend people’s lives, cause enormous stress, and lead to debilitating personal debt. The societal harm caused by mass layoffs has been known for decades. Yet, we do little to stop them.…

Read MoreWhat does facing the beast mean? In this time of uncertainty, we must practice regular reflection to achieve optimal happiness and health. The metaphor below gives insight into confronting and facing it, regardless of what “the beast” is to you. The following is. an excerpt from Facing the Beast by Naomi Wolf. It has been adapted for the…

Read MoreWe’ve all heard of the phrases “time flies” and “time heals all wounds,” but what really is time, and how does it impact our lives? The concept of time may be even more powerful than we think, especially when it comes to the money we save and spend. The following is an excerpt from The…

Read More“Climate change asks us questions that climate science cannot answer,” — Dougald Hine When it comes to climate change, it seems as if there are always new questions arising: How did we get to this point? How can we stop it? What’s next? Unfortunately, there is no black-and-white, straightforward answer to any of them —…

Read More