To Garden is to be Resilient

Our gardens provide many things; food for our tables, flowers for our loved ones, even a pleasant way to spend sunny afternoons—but there’s so much more we can gain from our gardens. While we’re planting, weeding, and watering, we’re doing so much more than growing. We are building resilience, from the ground up.

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Y2K

Many people got very worried toward the end of 1999 as the year 2000—and the so-called Y2K event—approached. They feared that a computer glitch would bring modern society tumbling down, at least temporarily. They spent a lot of money buying expensive and bad-tasting commercial dried food and expensive backups for their computers. I didn’t. Bad-tasting food still tastes bad in hard times. One might have to make do with bad food in hard times, but I never arrange for bad food deliberately. Any arrangements I make involve eating well. As Y2K approached, I did precisely nothing. Because of my special dietary needs and how they had shaped my gardening interests, by 1999 I had a garden full of overwintering vegetables, bags of potatoes in the garage, and a pantry full of dry corns, beans, winter squashes, and dried squash—all of gourmet quality—plenty enough for my own family and neighbors besides, at least for a while. I already had equipment for grinding the corn. I had already developed the recipes. Growing and using these staples was an ordinary part of my life.

And as for my computer . . . it had always had a hard time with time. By Y2K, my computer was about two years behind. I figured what it didn’t know wouldn’t hurt it. Sometimes different kinds of hard times cancel each other out.

We gardeners already know that we can grow much better food than anything we can buy in the grocery store.

This is even truer for staples than it is for the more ordinary garden vegetables. So I grow some of my own staple crops. It’s deeply satisfying. Doing so enhances my emotional as well as physical resilience. It gives me greater control over my food supply. My small, private, individual resilience translates into resilience writ larger, however. I don’t grow and store staples because I’m expecting civilization to collapse within the next season so that I need the stored staples in order to keep from starving. I do it primarily because growing and using those potatoes, corn, beans, and squash provides superb food of a quality I can’t buy, personal satisfaction, and greater joy and health for myself.

If some kind of major disaster were to hit my world, though, a few hundred pounds of dry corn and the equipment and knowledge needed to turn them into human sustenance might make a big difference for me and my neighbors. The resilience of individual gardeners working for personal satisfaction and joy in ordinary hard times (such as having special dietary needs) can thus be transformed into resilience during more extraordinary hard times, for both the individual and his or her community. Life is full of hard times. By learning to garden our way through the small and ordinary hard times, and by passing that knowledge on, we can help our children, our children’s children, our country, and our species through both the ordinary as well as the extraordinary hard times that happen through the generations.

Practicing Balance

As it turned out, pretty much nothing happened on Y2K. I don’t know whether it was because all the major companies managed to fix their computers in time or not. This I do know: There are many kinds of disasters we can foresee, and many or most of them never materialize. Even if they do materialize, it might not be in our lifetimes. Disasters also happen unforeseen.

But we don’t get our choice of hard times. You could spend huge amounts of time and money stockpiling things for the disaster you expect, and instead get a disaster such as a fire, when what you need to do to survive is to forget all those supplies and evacuate. Furthermore, living too much in the future is emotionally unhealthy. It’s important to position ourselves and our societies so as to enhance our resilience in good times and bad, and that requires some advance planning, learning, and exploration. We also need to enjoy life and to live fully. For that it’s important to live primarily in the present.

In hard times, I might not have electricity for watering or irrigation. So I learn how to minimize the need for electricity and irrigation in my current gardening. But I don’t try to do without electricity entirely. I have shifted my gardening so as to minimize the need for irrigation as well as to get the optimum use out of the irrigation I do apply. In this way, I enhance my ability to garden in any potential future hard times, but I also garden more efficiently in good times. I avoid wasting water, which means that I also minimize the electricity required to pump it and the labor involved in watering. Excess water leaches out some soil nutrients, also. So minimizing watering and avoiding unnecessary watering helps minimize my fertilizer needs. It allows me to have a smaller ecological impact on the land. It makes me a better, more ecological, more efficient gardener, in good times and bad.

Hard times might make fertilizer unavailable. So I learn exactly how much fertilizer I need in what situations, when I can getaway without fertilizing at all, and how I can best use the resources I have to retain and enhance fertility. This means if I suddenly need to do without any external inputs for a while, I’ll know-how. It also means that I avoid overfertilizing, thus saving money in good times. By not overfertilizing, I avoid polluting in good times and bad.

While mega-hard times are likely over the next thousand years, you personally may never need to deal with anything more than a broken leg or your city limiting yard and garden watering temporarily because of a minor drought. To the possibility of hard times of all sizes and kinds, I suggest a gentle, moderated response. Your current gardening is most likely based upon the assumptions that things will continue in the coming years as they have in the past, that society will remain intact and functional and bring you rototiller parts, gas, fertilizer, and seeds, that you will always have plenty of water and electricity for irrigating, that you can easily buy all the foods you want, and that you can consider growing and preserving food as primarily a recreation or luxury. I suggest you devote a portion of your learning and practice of gardening to all the opposite assumptions. Continue to focus primarily on your ordinary life and your ordinary gardening. But also learn and play and adventure in your yard and garden so as to increase the resilience of your yard and garden and yourself. Continue to give your primary attention to your ordinary life and to full enjoyment of the present, however. Your first job in surviving any possible future hard times is to survive long enough to get there.

Appropriate Self-Sufficiency

How independent should we be?

How independent should we want to be?

And of what and whom?

Many people who become aware of the uncertainty of life and the reality that hard times happen respond by going somewhat overboard. They assume, for example, that a breakdown in the social fabric through social or physical disaster would mean that they would have access only to what could be provided in and by their immediate neighborhoods. In fact, humans have never been so limited. We weren’t so limited before we had horses, oxen, and wheels. We aren’t now. If a major disaster were to destroy our current means, methods, and patterns of trade, I am confident that it wouldn’t take us long to create new ones. To err may or may not be human, but to trade definitely is.

Humans have been trading for millennia. For instance, the best obsidian and flint for making tools is found only in certain places. Throughout the world, it was always widely traded beyond those places. Here in the Pacific Northwest there were regular trade bazaars held at certain times of year. Coastal and Columbia River tribes traded dried salmon to inland tribes for dried camas-root cakes, dried elk meat, and other goods. Lewis and Clark passed over the mountains on a road made by Indian traders. Navigable rivers were major trade routes. Rivers and oceans have always been thoroughfares for trade, and many settlements grew up on and near waterways. Those waterways are still there. Even in the worst of all possible scenarios there would still be rivers, oceans, lakes, waterways, traders, and trade. I don’t see humans having to depend more than temporarily upon only their own skills, talents, and immediate local resources. Instead, I imagine them rapidly rebuilding societies from whomever and whatever is left, and quickly setting about to do what they have always done—specialize, swap with neighbors, and trade over seriously long distances.

Is “independence” even a virtue?

It seems to me that, to be truly independent, I would have to love and care about no one, and be loved and cared about by no one. And I would have no one to learn from and no one to teach. It’s a depressing image.

Humans are inherently social creatures. Even those of us who are relatively serious loners are only loners intermittently. We are all parts of a complex web of relationships and mutualisms. It isn’t normal, natural, or healthy for us to be “independent.” What is healthy is interdependence. In ordinary and good times, we don’t really seek true independence, but rather, enough knowledge and skills so that we can build and hold up our end of honorable interdependence. I think the same applies to even mega-hard times. We don’t need and need not bother wanting to be “independent.” Instead, we need the kinds of knowledge and skills that allow us to be valuable and contributing participants in honorable interdependence in both good times and bad.

Gardening—an Essential Survival Skill

There are some things everyone should know in order to be a fully functional and productive member of society. Some of these skills define adulthood. Mastering them is part of becoming an adult. Others require decades of further living for full mastery, and mark the transition from mere adulthood to wisdom.

Everyone’s list would vary somewhat. Here’s mine:

You need to be able to walk, run, stand, and crawl. You can read, write, do basic arithmetic, and type. You can drive, swim, perform first aid, use contraception, deliver a baby, tend the old or ill, comfort the dying. You are able to support yourself. You wash your hands. You are courteous. You function at least adequately in an emergency, perhaps excellently, and you know the difference between an emergency and an inconvenience. You can give orders, take orders, lead, or follow, and you know when to do which.

You either don’t drink or can hold your liquor. You know when to speak and when to be silent. You know how to listen. You know how to say, “I’m sorry,” and mean it. And “I was wrong,” and mean that too. You can build a fire. You can cook a delicious meal from simple basic ingredients. And you can garden.

You can garden. You know how to grow food, including some staples. You may not garden every year of your life, but you at least know-how.

Knowing these things promotes individual personal happiness and survival—survival physically, emotionally, and spiritually. A community in which many people know these things is a healthy and resilient community—a community that is maximally positioned to thrive in good times and to survive the rest.

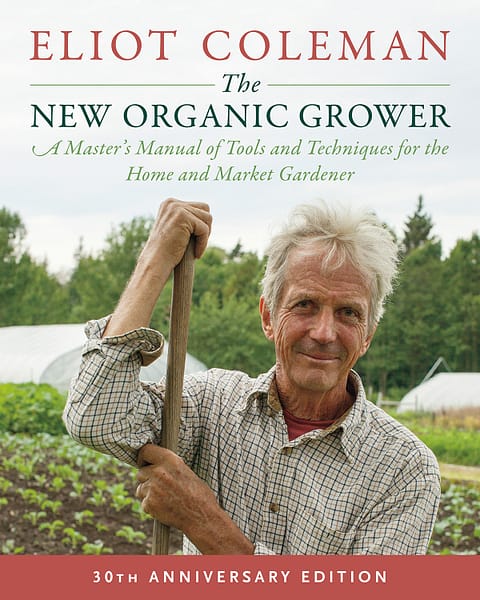

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Nothing says “spring” like a fresh, foraged meal! Savor the flavors of the season with this Milkweed Bud Pizza recipe.

Read MoreOxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreSo you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start? Learn how to break down the options of harvesting tools!

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read More