Seeing the Trees for the Forest

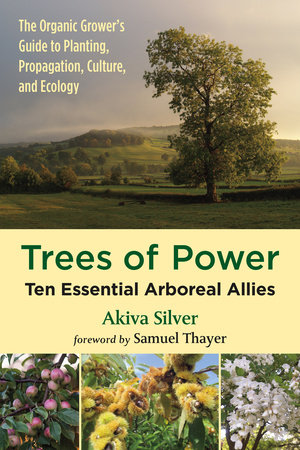

In the opening chapter of Trees of Power, author Akiva Silver sings the praises of tree identification. He first describes the skill as being “as useful to me as reading,” and later promises readers that in learning to discern trees by their bark, twigs, leaves, and silhouettes, “you will be able to read stories in the landscape.” I find neither statement by Silver to be fanciful or hyperbolic.

When I first began learning to identify trees in earnest, the experience was revelatory. It wasn’t just the discovery that basswood buds resemble puffin heads, or that the bark plates of elder sugar maples curve away from the trunk at their vertical edges, while those of aging red maples shag outward from the horizontal. My world grew bigger.

I suddenly noticed trees that had surrounded me all my life, rather than simply seeing “the woods.” And the yellow birches, American beeches, and chestnut oaks did (and do) indeed tell me stories: of 500 year-old storms, of former sheep pastures, of sapsuckers, pine weevils, and fire. General terms like “trees” and “forests” are necessary for efficient communication, but alone flatten the incredible diversity of both species and individuals.

As an editor, I feel the same way about the word “books.”

It’s a great privilege to every day be surrounded by books—the books arrayed on the shelves behind my desk; books packed into boxes that arrive in the office daily; the various archival libraries of Chelsea Green dating back to 1985, curated for different purposes by different departments—but describing what I do as “working with books” or “editing books” can feel like reducing a floodplain full of silver maple, box elder, sycamore, and river birch to “trees.”

Technically correct and fine in a pinch, but working at a small, independent publisher has given me insight into books not as faceless commodities, but as individuals with unique, complex origins and stories to tell beyond those within their pages.

There are stories of how the author found the publisher, or vice versa. There are stories behind the cover design, the choice of typeface, the color of the endpapers, the photography, the title, the marketing strategy, the outreach to endorsers.

An author might have stories about trying to make their deadline, about bursts of inspiration and the frustration of writer’s block. An editor could tell you stories of discovering someone doing tremendous, world-changing work in their field, and of praying, Say yes, say yes, say yes, say yes when making an offer for their book. Perhaps most importantly, each copy of the same book in the hands of a different reader itself becomes something unique, affecting each reader’s life in a different way.

And, of course, every book printed on paper also contains within it the stories of trees, the people who planted them, the birds and mammals that dispersed their seeds, the insects that pollinated their flowers, the vast networks of fungi and microorganisms interacting with their roots, the climate, the elevation, the aspect. Not to spoil the end of Silver’s book, but the last sentence is “Happy Planting.” To that I’d like to add “Happy Reading.”

By Michael Metivier

Michael has been an editor at Chelsea Green Publishing since 2013, joining the staff after earning his Master of Science degree in environmental studies from Antioch University New England. His editing projects have included best-selling and award-winning titles such as Eager, Pawpaw, and Farming While Black. He is also a poet whose work has been published in Poetry, Crazyhorse, North American Review, and African American Review, among other journals. He lives on the north side of Vermont’s Mount Ascutney with his wife and daughters.

This excerpt is from the 2019 Summer Magazine. It has been adapted for the web.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

You know of Dasher, Dancer, Prancer & Vixen. Comet, Cupid, Donner & Blitzen. Rudolph too! But have you heard of the Sámi people who herd reindeer in Norway?

Read MoreNo heated greenhouse? No problem! Discover the secrets to thriving winter gardening without breaking the bank.

Read MoreWintergreen is the stunning evergreen groundcover that’s a game-changer for your garden! It’s cherished for its aromatic leaves, vibrant fall color & bright berries.

Read MoreYear-round growth without the hefty price tag of a greenhouse? Low tunnels are the cost-effective and flexible solution you’ve been looking for. Grow year-round with low tunnels!

Read More