Site Repair: Using the Land’s History

Buying a new property is exciting. You might have hundreds of ideas running through your head about where you want to put buildings or clear away trees or start planting. Immediately starting these projects may not be in your farm’s best interest, though, and can drastically impact the landscape. Often, features like meadows or ponds are meant to be left alone and given space because that’s the way nature intended it to be. If you do want to make changes, look at the history of the land first and take into consideration what is already on the land.

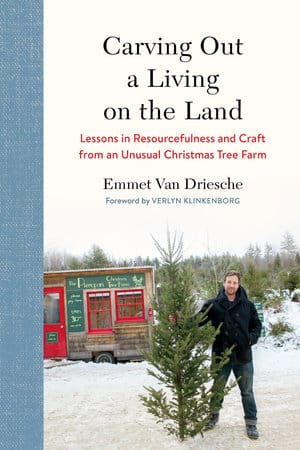

The following is an excerpt from Carving Out a Living on the Land by Emmet Van Driesche. It has been adapted for the web.

Understanding the history of your land is not about preserving the past like in some museum, unless that is your thing.

Rather, it serves as a jumping-off point, learning what made sense then to think about what makes sense now. It is easy to dwell on the mistakes of past landowners (if they hadn’t made any, their descendants might still be farming the land and not you), and fail to see the excellent choices that were made in siting buildings, defining pastures and woodlots, and utilizing springs.

When we moved into our farmhouse, I spent the first couple of years daydreaming about all the changes I would make to the house if we ever bought it, only to realize that my first ideas were not that good, and that I had reacted to the landscape without any sense of nuance. As I observed more and lived through more seasons, my understanding of what would make the house better changed. Although we didn’t end up buying the house, it was a lesson I took to heart.

The concept of site repair offers another way to think about our propensity to make too many changes, too fast, when encountering a new landscape.

After all, it is such a lovely meadow. But sometimes adding to a space destroys or disrupts the very things that made it lovely and took years or even decades to develop, including plants, the way animals interact with the landscape, the way the wind blows across it, or a view. Buildings are not bad; they can vastly enrich the spaces around them if sited and built thoughtfully. But they inevitably disrupt what was there before, and so the best thing is to site them, if possible, in an area in need of repair.

According to the site repair principle, the broken-down wreck of a building that is slowly moldering into the goldenrod gets removed and cleaned up to make way for building something new, and the meadow stays the lovely meadow that took so many years to evolve.

Site repair is not commonly practiced on farms, in part because there is usually more land available than there is money to clean up the old foundation, and in part because we farmers are thrifty. That jumble of old equipment on the field edge? It might provide us with a part we need someday, or we might be waiting for the price of scrap metal to go up, or we see it as some sort of crazy retirement plan to eventually sell. In the meantime, we plunk the new greenhouse or shed or barn or house, even, right in the middle of the nicest bit we’ve got.

This is exactly the sort of short-term thinking that gets farms into trouble. What would you do differently if you were to create a five-year plan for your farm to be as successful as you hope and imagine it could be? What about a ten-year plan? Twenty-five? The best farmers make the big decisions using the history of their land to inform long-term future moves, while also reading the tea leaves in the present to keep things moving in that direction in the short term. This can mean new infrastructure using site repair, but it can also mean repairing and using the structures that already exist, whenever possible.

Cecilia and I did a lot of repurposing of spaces when we lived at the farm, and we continue to do it at the house we now own. When we needed a garden shed, I mucked out the old outhouse, put a new floor down, repaired the broken window, and built a door. When we needed a space to make wreaths and cure garlic, I emptied the little greenhouse shed of its junk, repaired the roof, and repainted it. We cleaned and organized several areas in the big barn to create space to store poles of wreaths during the wholesale season, and we dismantled another shed that had collapsed down a gully rather than just let it rot in place.

Landscape Design for Site Repair

Whenever you are adding a new structure to a landscape or renovating an existing one, here are some basic principles to keep in mind:

- Whenever possible, rehabilitate the worst piece of land with any new construction. This might mean ripping down that

scary old barn, or it might mean repairing and adding to it.

- Pay attention to solar orientation and prevailing winds to create warmer and cooler microclimates in the winter and summer. The particulars of this vary from climate to climate, but local vernacular architecture usually features ingenious solutions for this, so if in doubt do some research and make field trips to good examples.

- Orient new structures so that the area formed between them becomes a useful, usable space. Often this means deliberately building structures closer together, which can in turn be used to create sunny spots out of the wind or pools of shade facing the prevailing breeze.

- Be aware of the potential for any structure to be useful around its entire edge. Design an outside that creates opportunities for storage, work, or relaxation.

- If there are trees on your property, be wary of siting buildings under their potential fall path, particularly trees like white pine (Pinus strobus), cottonwood (Populus deltoides), and poplar (Populus grandidentata) that are prone to snapping and falling. If they are leaning, build on the side away from the lean or remove the trees.

- Consider the workflow of your farm. Site your buildings and structures to make your operation run as efficiently as possible, within the constraints of your land. If your operation is by necessity spread out, concentrate as many operational tasks into one spot as possible, but make sure tools and supplies are close at hand for each task. Sometimes this means separate toolsheds or walls for far-flung fields. Sometimes (as with me) it means that everything rides along in the truck from location to location.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Planting cover crops is a key step in transforming dirt into soil! The benefit list is long but they need to be selected with a purpose.

Read MoreMulch is essential to soil health. It acts as a barrier against water loss and heat, reduces weeds and improves soil structure. Its an easy way to boost your soil’s health!

Read MoreWith more than 80 percent of the US population now residing in urban areas food forests help provide a local food source. And they also serve as perfect platforms for community-building.

Read MoreWeeds are the bane of every farmer and gardener’s existence. Before you go crusading against the weeds in your garden follow these tips and tricks!

Read MoreWith these easy tips and tricks, you’ll be prepared to successfully harvest and store the cucumbers until they’re ready to eat.

Read More

scary old barn, or it might mean repairing and adding to it.

scary old barn, or it might mean repairing and adding to it.