Building Your Backyard Permaculture Paradise

The award-winning Paradise Lot takes a behind-the-scenes look at how two plant geeks transformed a desolate urban backyard into a permaculture paradise. At the same time, the pair were hoping to each find their own Eve for this special garden adventure. They succeeded on both fronts–creating an urban, food-producing oasis on a tenth of an acre, and finding life partners.

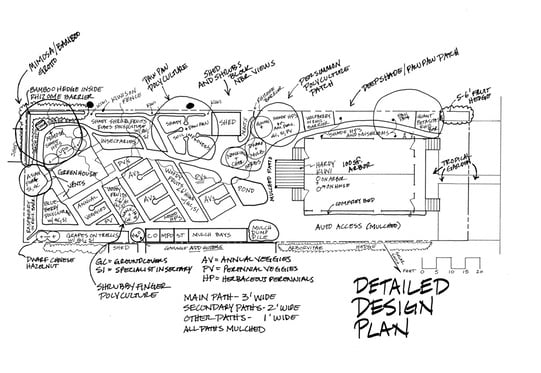

As you look out on your (barren) backyard, here is how Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates approached those initial phases of transformation–along with their site designs. We hope this excerpt provides you with plenty of spring planting ideas and inspiration for the coming gardening season.

GUILD-BUILD

One of my favorite phases of any design is assembling a species palette, a master list of all the species you might use to paint a living and productive landscape onto your site. The “guild-build” process that Dave and I developed for Edible Forest Gardens helps gardeners assemble a master list of species for all necessary niches.

The first phase of guild-build is to make a list of all the things you hope to grow. The woody plants Jonathan and I were most excited about were American persimmon, pawpaw, chestnuts, Asian pear, and hardy kiwifruit. We already grew most of the herbaceous species that we were keen on, from good King Henry to strawberries and perennial ground-cherries.

After you have analyzed your site, you look at your list of desired species to see what’s realistic and what’s not. Sadly, some species are usually cut at this point. For us, the list was long and, particularly with the trees, impossible. There simply would not be space for chestnuts: the two full-size trees required for pollination would fill up almost the entire yard. We also regretfully closed the door on nut pines, the macadamia-like nuts of yellowhorn, and figlike che fruits. In fact, given the small size of our lot, we were going to have to work hard to achieve our goal of a double handful of fresh fruit every day from May to October.

To do that, we would have to focus primarily on fruiting shrubs and dwarf trees. Besides space, our other primary limitation was shade. We were going to be able to grow only a few species that required full sun; we had more room to stretch out and explore the range of shade-loving edibles.

Another part of the guild-build process is determining what uses and functions are called for and cross-checking it against the list of everything you hope to grow. We were going to need groundcovers, nitrogen-fixing species, and insect nectary plants. Jonathan and I looked for gaps in our list based on the roles we wanted our plants to serve in the garden. Did we have nitrogen-fixing species for shade? Had we included any evergreen groundcovers? We went back to the tables in Edible Forest Gardens (still unpublished at this point) to select species to fill the niches that we had left open.

Jonathan and I were guided by the principle that everything we planted should have multiple functions and should be edible whenever possible. We also wanted to begin our search with native species and expand outward from there. The challenge was that maximizing diversity was also a priority for us; we wanted to sample the range of possibilities, especially for smaller plants like herbaceous perennials.

Jonathan and I knew there would be core native edibles in our garden that would serve as anchors in our species palette. The native fruits we chose to include were American persimmon, pawpaw, beach plum, clove currant, various blueberry species and hybrids, multiple juneberries, and many more—a total of twenty native fruit species in fifteen genera.

Not bad for a tenth of an acre. We set out for about half of our garden to be natives, which would mean a hundred or more representatives of the eastern flora.

Most nut trees were too large for our garden, but we tracked down two chinquapins (native bush chestnuts) from a small nursery in Georgia. And we included many species of native herbaceous wild edibles, from sunchokes to giant Solomon’s seal. Though none were as far along in domestication and productivity as a perennial like asparagus, we felt it was important to include them. From nearby forests we collected seeds of native nitrogen-fixers, like tick trefoils, hog peanuts, and wild sennas, and nectary plants, like the impressive cow parsnip.

Collecting seed of wild plants is fun and, as long as the plants are not rare and you leave plenty of seed, nothing to feel bad about. In fact, by taking the plants into cultivation, I feel we are reducing pressure on wild stands. I’d been exploring the areas behind bowling alleys and beneath highway overpasses for a decade and knew right where to watch while driving by. When I saw seed drying, we pulled over (perhaps sometimes recklessly) and added to our collection.

Our search for multifunctional species led us down some unexpected paths. For example, we didn’t feel we could sacrifice much space to nitrogen-fixing plants that were not also providing food. This led us to hog peanuts, a shade-loving native with edible underground beans. They are quite lovely and often seen alongside the path on New England hikes, but except at Tripple Brook Farm I had never seen hog peanuts growing in anyone’s garden. It is the perfect example of an underappreciated native species, which gains importance in a garden that prioritizes multifunctional plants to fill specific niches.

Not all of our choices were as easy.

For example, there is no eastern native nitrogen-fixing shrub with decent edible fruit. We asked ourselves what we should pick instead: a native nonedible like sweetfern, a nonnative edible like goumi, or even a nonnative nonedible like Siberian pea shrub? Given our space constraints, we went with goumi, a relative of the maligned autumn olive, because it both fruits and makes fertilizer, which no Massachusetts native species could do. This medium-sized Asian shrub is a great nitrogen-fixer and grows well in the Northeastern United States.

Up until we completed the species palette, Jonathan and I did not need to show much originality in our design. Our goals were our own, but the final analysis and assessment map we created, though it included a few suggestions about what might happen where, was basically a final report to ourselves about our yard.

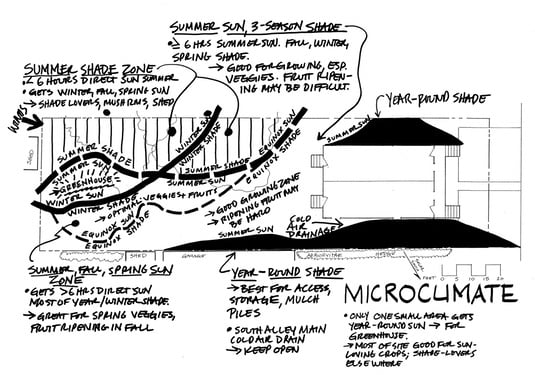

We decided to use the south alley for our access road: both alleys had equal shade and width, but the southern alley would do a better job draining frost from our garden.

Its bad soil and full shade made it ideal for offloading and storing piles of compost and mulch. The north side of the garden, with summer shade, would become our woodland edge habitat, with shade-loving species like pawpaws, gooseberries, and wild leeks growing under Norway maples. We would build a shed in the area with terrible clay soil and summer shade on the north side of the property.

We already knew where our greenhouse had to go: in the small year-round sunny spot between the summer sun and winter sun areas, and we decided to lay our main path leading from the house to the greenhouse along the line between the summer sun and summer shade areas. The summer sun areas would mimic the old-field mosaic habitat behind Kmart and feature shrub and perennial beds alternating with annual beds.

It was clear that Jonathan and I had found the challenge we’d been looking for. Could we bring about an edible paradise on our blighted lot? Could we regenerate soil, bring back birds, and meet all of our goals on only a tenth of an acre without cramming everything in too tight? And might we ever meet women who could appreciate guys who spent more time on the Plants for a Future online database than singles websites? Time would tell.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

The Netherlands is ranked second in agricultural export volume behind the United States. Their secret weapon? Greenhouses and hoophouses.

Read MoreDitch the big garden myth! 🌱 Think you need an outdoor garden to enjoy fresh produce? Think again! Follow our quick & easy guide to harvest vibrant greens at home in just a couple of weeks, no matter your space.

And cold temperatures doesn’t have to mean the end of fresh greens. You can enjoy vibrant greens year-round!

Read MoreGet ready for a bountiful harvest! Storing seeds is the key to having a successful growing season. Follow these tips to keep your seeds organized and ready to plant 🌿🪴 Get ready to plant like a pro this season!

Read MoreThese hardy little berries are great to grow if you live in a colder climate. A versatile evergreen ground cover that bring both ornamental beauty and productive harvests to acidic-soil gardens.

Read MoreExtend Your Growing Season with a Cold Frame! Plant earlier in spring AND grow later into fall. Build your own cold frame and enjoy a longer harvest season! Ready to grow more, longer?

Read More