Young Farmers: Back to the Land and Down to Business

If you haven’t been working on a farm since childhood or weren’t lucky enough to inherit one from your family, it can be difficult to build one from the ground up. Farming takes more planning and thinking than meets the eye, but it’s not impossible. We’ve got aspiring young farmers covered with how to proceed with your dream.

The following is an excerpt from Farms With A Future by Rebecca Thistlethwaite. It has been adapted for the web.

I don’t care if you are 18 or 58, an urbanite or a country gal, you all have one thing in common: You have a desire to be a farmer but limited years of experience doing it—you’re what some might refer to as a “greenhorn.” You need resources and support, as well as mentors, friends, and family you can draw on for inspiration and know-how, or perhaps for startup capital and good old-fashioned extra hands. I have been a beginning farmer myself (and might even still be classified as one under USDA definitions), as well as worked alongside and conversed with hundreds of beginning farmers across the country to get ideas for this book. Here, in a nutshell, is what I have concluded from their collective wisdom:

1. Dabbling in farming is fine when you start—in fact, it is encouraged. But don’t go too long without creating a plan.

2. Writing a formal business plan is a good mental exercise and will be instrumental if you want to apply for financing later on in your business evolution, but when starting a new business you can expect a lot of change in those first few years. Unless you intend to draft new editions of the plan with every twist and turn, your business plan may become obsolete immediately. Shoot for having a fairly ironed-out plan by year three. Make sure you include all members of your family in the planning process if they have a role or stake in the business or intend to in the future. More than likely, you will not be doing this alone. Communicate with all the likely stakeholders.

3. New businesses rarely make money in the first few years and often lose money while they are gearing up production and working out the kinks. Have a survival plan for those first few years of loss, and try not to borrow against your future profits because, if you do, you may never get to profitability when your cash flow is too tied up servicing debt. If you are continuing to lose money into your second or third year, you should do a thorough analysis of your business model to understand how you can turn that around. Actually, do an end-of-the-year analysis every year until you start to turn a profit. A more in-depth discussion on financial management will come in later chapters.

4. A farm is a business. If you don’t want to run a business, consider gardening or homesteading instead. You will have to understand such things as profit and loss, assets and liabilities, and supply and demand and do basic bookkeeping. If these things scare you, that’s okay, but be willing to learn about them.

5. A farmer need not be poor. It is reasonable that you should be paid for your time and effort and that you make enough money to put away for a rainy day or retirement. You are your farm’s greatest asset—make sure you protect that asset! So plan for profit right from the beginning.

6. Start with the market in mind. Spend time researching potential customers, market channels, food fads, and so on. Look for gaps in the local food market that you might fill. Begin thinking about how your products will be different, superior, and so forth—more on this subject in the next chapter.

7. A garden or homestead is one of the best places to test your farming ideas. So is working for other farmers. Start small, build your skills, learn what grows best in your soils and climate, and figure out what you actually enjoy. If you can’t stand the behavior of a couple of sheep, you may not want to become a sheep farmer. If you hate bending over all day, you may not want to become a strawberry farmer. If baling and putting up hay turns you into an allergic mess of snot, you may not want to make hay for a living. Figure out what you like and excel at, and begin with those enterprises. You can always add or even delete enterprises later, but make sure you develop your farm around activities that bring you some joy or satisfaction.

8. If you wanted to open up a new restaurant, you would want to have some capital to do so. If you sought to build a new widget factory, you would want to have some capital to do so. If you want to start a farm, you might want some capital to do so. This may be hard if you are young and have a limited number of years working and saving money, or you are older and just barely getting by. However, you can start farming part-time while you work an off-farm job (indeed, 70% of American farmers do this), earning income that will support your basic living expenses and provide some capital for startup costs. Unlike many other businesses, you can also use the power of social capital to start your farm: Many people enjoy helping farmers by lending money, sharing equipment, or even providing volunteer labor. Much more on this subject later.

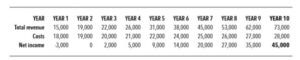

9. Start thinking about the scale of your business right when you start. A great exercise to get you thinking about scale is to project how much income you would like to make in years 5 and 10 of your business. Work backward from there to understand how much total revenue you need to make in those years to earn you that income. Then begin planning budgets from year 1 to year 10 to understand how you will have to scale the business to get to those numbers. A rudimentary example is charted below, which assumes that your goal is to make $45,000 in net profit by your tenth year of business:

What is a typical beginning farmer narrative? There is so much diversity in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, and geographical origins of today’s beginning farmer that no beginning farmer is “typical.” Many aren’t even coming from agricultural backgrounds or a historical family farm anymore. However, I think the two things that unite all beginning farmers are their enthusiasm and their fresh ideas.

Recommended Reads

Why Farm Infrastructure is Important: A Farm is More Than Land

Recent Articles

Now is the perfect time to start planning your garden. The location of your planting site is key to a thriving garden and one of the first things to consider!

Read MoreLooking to simplify fieldwork on your farm or homestead? The key is to act like a tree: stop working so hard and let nature do some of the work for you.

Read MoreSeed savers raise your hands! Picking the right seeds can make or break your garden. Learn some easy tips on how to choose the best seed crop for a thriving garden.

Read MoreGarden goals ahead! Planning is everything. Get ready to transform your outdoor space. Here are some tips on how to plan the best garden this growing season!

Read MoreTips for Seed Saving · Ready to unlock the power of seed saving? You either have dry seeds or wet seeds. Proper drying & storing is essential so they can germinate months (or even years) down the road. Begin your seed-saving journey today!

Read More