The Man Who Loved Labor And Hated Work

In response to one of the nation’s darkest labor-history chapters, Congress passed a law in 1894 making the first Monday of every September “Labor Day,” to pay tribute and honor the achievements and contributions of American workers.

While the passing of the law helped to improve conditions, standards, and relations there was still work to be done.

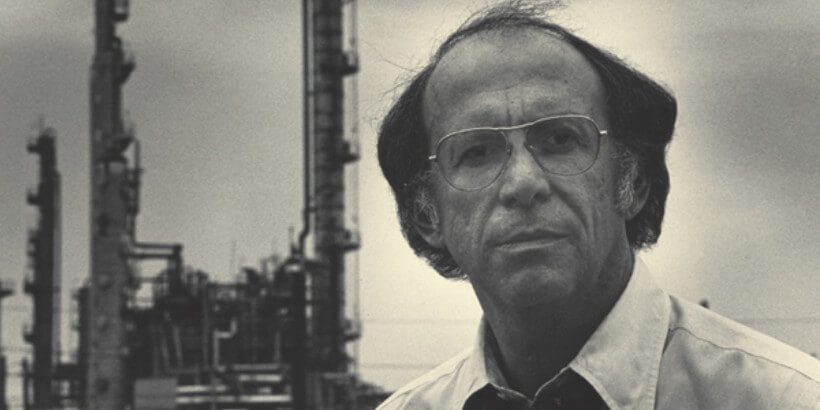

On Labor Day, we want to remember and honor the story of labor leader Tony Mazzocchi, who dedicated his life to fighting for the rights of workers, and whose efforts led to the passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

The following excerpt is from The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor by Les Leopold. It has been adapted for the web.

I first met Tony Mazzocchi a few months before he met Karen Silkwood.

I was a graduate student who had come to his cramped union office on 16th Street in Washington, DC, hoping to enlist in his radical occupational health and safety movement. Tony had other plans for me and for the movement.

His idea was impossibly simple—and perhaps simply impossible. He wanted to build a new working-class economics crusade, and he wanted me to help.

“Look,” he said, “I think the post–World War Two boom is over. Workers should be ready to learn about the problems of capitalism.”

All I had to do was follow the same steps Tony had taken to launch the health and safety movement. First we’d design a course.

Then we’d write a popular book based on the course. “Just don’t use a lot of Marxist jargon,” Tony said. Presto, a new movement would be born! I tried to believe him.

That fall, David Gordon, the noted radical economist, piloted our new political economy course for members of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union (OCAW) at the Rutgers Labor Education Center in New Jersey.

No surprise: We did not spark a mass movement. But it did lead in 1975 to the creation of the Labor Institute in New York.

Tony’s method for radical social change was joyous and communal, involving stimulating conversation and lots of raucous meals with friends.

As early as the 1950s, when the term environment was nowhere on the political radar, Tony learned about nuclear fallout and began integrating environmental concerns into his critique of capitalism and his union work.

His environmental radicalism grew in the 1960s and ’70s when he realized that corporations were willingly exposing workers to toxic, even lethal, substances to increase productivity and profits.

In the late 1980s, Tony was arguing that global warming might force us to fundamentally alter capitalism.

He believed that the struggle of capital against nature was the irreconcilable contradiction that would force systemic change.

For me, Tony conjured up a labor movement that didn’t really exist, but just might.

This movement would be militant and green. It wouldn’t just fight to protect the workforce from toxic substances—it would eliminate them. It would bring about radical changes that would stop global warming.

It would give workers real control over the quality and pace of work and over corporate investment decisions.

It would champion the fight against militarism and for justice and equality. It would win life-enhancing social programs such as free health care.

It would dare to create a new political party to counter the corporate domination of the two major parties. In short, it would make good on its potential to transform American capitalism into something much more humane.

When Tony talked about broad social programs, there were no sectarian overtones and no ’60s hype. He poked through the accepted wisdom that our inequitable, unsustainable economy was the best system that had ever been and could ever be.

He would continually ask why millions of people were stuck in low-paying, dead-end jobs—and why even good-paying jobs sentenced workers to so many occupational illnesses. He wanted every worker to have paid sabbaticals from work, a guaranteed income, and free access to higher education.

Tony’s big ideas led to Tony’s big actions—and both differentiated him from nearly every other modern labor leader.

He built bridges from the often insular labor movement to all the other major movements of his time—feminism, environmentalism, antiwar, civil rights.

He was instrumental in building the occupational health and safety movement, the environmental health movement, and alliances, as well as in creating a new generation of worker-oriented occupational health professionals. Thousands of workers’ lives were spared as a result.

He was anti-corporate to the core.

He thought that the drive for ever-increasing profits was in fundamental conflict with public health, worker health and safety, and a sound environment. He feared that growing corporate power could lead to authoritarianism.

The antidote was growing democratic unions with an active rank and file. Most of all, he thought we had it all backward: The purpose of life was not to toil until we dropped to enrich someone else. Rather it was to live life to its fullest by working less, not more.

Then why didn’t Tony Mazzocchi become a household name?

Why didn’t he succeed in turning the labor movement upside down? Maybe he was blocked by his fearsome enemies—including CIA operatives in his own union. The nation’s most powerful corporate interests, from Big Oil to the nuclear industry, didn’t like Tony very much, either.

Or maybe he was just too principled. His friends worried that he was too idealistic and pure to grab power when it was there for the grabbing.

Tony Mazzocchi hoped to lay out the stepping-stones to lead future generations to a healthier and more equitable society. I hope this book will help those generations, as they move along those uneven stones, to take courage from the audacious dreamer who put them in place.

Recent Articles

Why is modern wheat making us sick? That’s the question posed by author Eli Rogosa in Restoring Heritage Grains. Wheat is the most widely grown crop on our planet, yet industrial breeders have transformed this ancient staff of life into a commodity of yield and profit—witness the increase in gluten intolerance and ‘wheat belly’. Modern…

Read MoreUsing herbal medicine to heal the body is an ancient practice. It has since become a worldwide industry. Today, modern-day doctor’s visits and industrial medicine have displaced common knowledge of herbal medicine. Some still remember the ancient practice. In her book Following the Herbal Harvest, Ann Armbrecht interviews one such person, Phyllis Light, a fourth-generation…

Read MoreAddressing the pressing issues affecting everyday Americans is essential—and one of our nation’s most profound challenges is the devastating impact of mass layoffs. Layoffs upend people’s lives, cause enormous stress, and lead to debilitating personal debt. The societal harm caused by mass layoffs has been known for decades. Yet, we do little to stop them.…

Read MoreWhat does facing the beast mean? In this time of uncertainty, we must practice regular reflection to achieve optimal happiness and health. The metaphor below gives insight into confronting and facing it, regardless of what “the beast” is to you. The following is. an excerpt from Facing the Beast by Naomi Wolf. It has been adapted for the…

Read MoreIn a personal investigation into ethical and traceable leather, fashion designer Alice Robinson begins a ground-breaking journey into the origin story of leather and its connection to food and farming. Keep reading to learn more about her process of cutting & shaping leather to create handbags, shoes, clothing, and more! The following is an excerpt from…

Read More