Brewing California Sagebrush Beer: The Foraging Brewer

Hyperlocal brewing, making concoctions only out of the ingredients available in your immediate environment, is a fun way to become more familiar with your surroundings and the possibilities within them. According to wildcrafting author Pascal Baudar, “the number of possible ingredients you can use is mind boggling.” And the end results can be so rewarding!

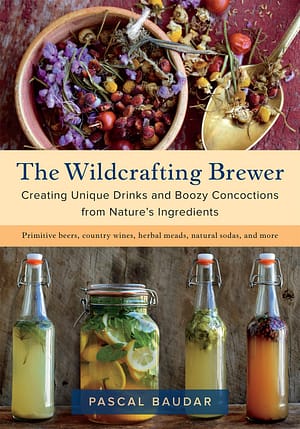

The following excerpt is from Pascal’s book, The Wildcrafting Brewer. It has been adapted for the web.

I enjoy creating alcoholic beverages using local plants, sugar sources, and even yeasts and bacteria to represent, through taste, the environments or regions we live in.

If you live in Vermont, Maine, or New Hampshire, you can create delicious fermented beverages or “beers” representing a specific forest, mountain, or territory by using what’s available in that location: maple or birch syrup, wild sassafras roots, spruce, birch bark, white pine, yarrow, turkey tail or chaga mushrooms, local yeast from flowers, wild berries, or barks, and so on. You could call it hyperlocal brewing. I’ve found from my own actual research and experience that the number of possible ingredients you can use is mind boggling.

Most of my alcoholic beverages—sodas, wines, and what I somewhat loosely call beers—are closer to fermented infusions of a sort: mixes of plants, sugar sources, fruits, and sometimes malted grains designed to achieve interesting flavors.

As a wild food instructor and culinary researcher, I tend to concentrate on what I call the true flavors of a local “terroir,” which, from my perspective, means using what can be found in the original landscape as opposed to nonlocal or recently imported plants and ingredients (which would therefore include such things as hops).

My approach was to study brewing from a forager’s perspective. It was an unusual point of view with a strong emphasis on utilizing what I was able to find.

You may think there aren’t that many things out there to brew with, but after many years of research and experimenting, I’ve found well over 150 possible ingredients that can be used in the creation of my wild beers and other fermented concoctions. We’re talking wild berries, plants, and barks; fruit molasses, tree saps, or wild honeydew as sugar sources; leaves, roots, wild yeast, insects, and much more.

One of the fascinating aspects of what I do is the fact that very often I realize that I’m not really creating anything new; I’ve simply rediscovered some lost knowledge. A good example is the use of willow bark as a bittering ingredient for beer. I thought I had an original idea when I used it in some of my beers, only to find out quickly that it was used in traditional medicinal beers and even still is used in Germany to make a specific style of beer (Grätzer beer).

On the other hand, you can discover new possibilities from time to time. For example, in Southern California there are few if any recorded native uses of local plants for alcoholic consumption, but we do have some very interesting species such as California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) and yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum). These are fantastic to flavor beers and were used medicinally as tea in the past.

California sagebrush is related to wormwood and mugwort, both herbs that were used instead of hops in older unhopped beer recipes. Yerba santa is a local aromatic herb that was used as a medicinal (cold and flu) tea. The flavor is really in the sticky sap, and if you boil it, you end up with quite a bitter tea. Because of these characteristics, both plants are used as bittering agents, like hops, in some of my primitive brews.

Maybe my own ancestors reached the same conclusion I did: There are no real rules! If it’s enjoyable, somewhat tasty, and does the job, you’ve done your work!

Recipe: California Sagebrush Beer

California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) is found in west-central and southwestern California and northern areas of Mexico. Locally, the plant has been used as a spice and also for medicine (cough, cold, and pain relief, and more). As an artemisia, the plant is related to wormwood and mug-wort, both used as hops substitutes. It’s the only “sagebrush” I know locally that has culinary uses. Like many hops substitutes, the plant is highly aromatic and bitter. I often use California sagebrush as an added aromatic in my horehound beer.

Ingredients

1 gallon (3.78 L) water

0.2 ounce (6 g) dried California sagebrush leaves

11⁄4 pounds (567 g) dark brown sugar, or

1 pound (454 g) dry malt extract

Zest of 1 orange

Commercial beer yeast or wild yeast starter

Procedure

- Mix the water, sagebrush, and sugar in a large pot. Bring the solution to a boil; let it boil for 30 minutes. Add the orange zest 5 minutes before the end of the boiling time.

- Remove the pot from the heat and place it in a pan or sink full of cold water. Cool to 70°F (21°C), then add the yeast (wild or commercial). When I’m using a wild yeast starter, I usually use 1⁄2 to 3⁄4 cup (120–180 ml) of liquid.

- Strain the brew into the fermenter. Position the air-lock or cover your fermenter with a paper towel or cheesecloth. Let the beer ferment for 10 days. Start counting when the fermentation is active (this may take 2 to 3 days with a wild yeast starter).

- Siphon into 16-ounce (500 ml) swing-top beer bottles (you’ll need seven bottles) and prime each one with 1⁄2 teaspoon (2 g) white or brown sugar for carbonation. Close the bottles and store in a place that’s not too hot. The beer will be ready to drink in 3 to 4 weeks. If you used dry malt extract, you can do a full fermentation then exact priming to achieve the carbonation you want.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Nothing says “spring” like a fresh, foraged meal! Savor the flavors of the season with this Milkweed Bud Pizza recipe.

Read MoreOxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read More