Community Food Forests in Action

Alright. We’ve covered the basics of what a community food forest is, how to plan one, and which approach is best. Now it’s time to see some in action! Keep reading to learn more about some of the pioneers of the food forest movement.

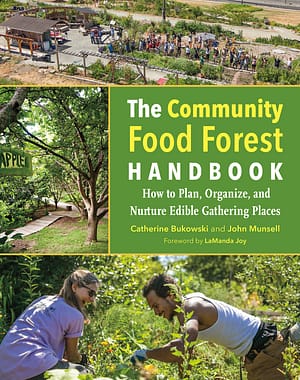

The following excerpt is from The Community Food Forest Handbook by Catherine Bukowski and John Munsell. It has been adapted for the web.

The Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Park – Asheville, NC

When studying community food forests for this book, we noticed that many teams describe their projects in terms of food literacy and accessibility, community health and well-being, and environmental sustainability. We also found that community change is part of the conversation, but unlike food forest design, details about exactly how leaders will do this and what they intend to change are often lacking. In the end, goals such as changing local food systems by installing a community food forest are immensely complex; they take time and involve multiple stakeholders with different viewpoints and responsibilities. Nevertheless, permanence and change are possible, but perseverance is necessary and a little serendipity helps, too. We know of no better example of this than what transpired at the community food forests in Asheville, North Carolina, over the past two decades.

Critically reflecting on food accessibility and nutrition among all community members is paramount when working toward change, particularly through community food forests. Successful teams are those that roll up their sleeves and get to work on the hard tasks of uniting organizations and individuals working on similar causes. Though the Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Park in Asheville was not immune to potentially fatal problems such as turnover in leadership, questions and concerns among public representatives, too much development too fast, and times of limited to no maintenance or use, its continued existence is a testament to the power of perennial food forest systems. When humans needed to step aside and sort out their own complexities and processes, the food forest in Asheville continued to grow and remained ready for the next step. By its very existence, in good times and bad, the community food forest contributed to change by offering a place where like-minded people could come together and push food accessibility and environmental health into the public eye.

The founders, Samantha and Jonathan, formed a nonprofit organization called City Seeds, and they quickly fleshed out many ideas for projects, one of which was an edible park initiative they called the Bountiful City Project (which was later renamed the Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Park). The goal was to combine elements of parks, community gardens, and permaculture to create edible public spaces in urban and suburban areas. The Bountiful City Project was innovative not because of what it would accomplish, but because of where it would work and who would be involved. It sought to retrofit public land and ensure full public accessibility through an innovative effort that would intentionally combine the concept of public commons with contemporary perennial landscape design inspired by permaculture. The collective processes used in sustainable development would be applied to work across diverse groups of civic organizations and public agencies.

Basalt Food Park – Basalt, CO

We share the Basalt Food Park story to demonstrate the power of community food forest teamwork through successful publicity and partnerships with municipalities. It also showcases the importance of perseverance among core project leaders and the role of earth-based businesses and agroecological experience in creating a diverse project. The teamwork and commitment among those involved with the Basalt Food Park provides a model snapshot of how people come to participate in a community food forest—and how to capture, channel, and amplify their motivation and energy. It is a parable of the power found when energy is focused on accomplishing goals rather than succumbing to the ups and downs of a project. The benefits of partnerships with municipalities are also on display. Project leaders worked with their town officials and other local natural resource technical experts to address challenges and nd answers to important questions about how to pinpoint important environmental and social benchmarks, mechanics, and assumptions that lead to strategic success.

Basalt Food Park leaders put human capital (experience, knowledge, and energy) to work as a means for investing in locally grown Basalt food and its gardens and gardener culture. They amplified the reach of their skill sets by tapping into relationships built through professional connections and interests. Lisa, who worked in a town agency, had access to the city’s equipment and resources. She was in a good position to communicate with town staff about changing a land easement on the park to help ensure that the food forest could be established. By virtue of teaching courses in the local school system, Stephanie was connected to educators and was able to quickly make use of the site and show its educational utility. Both women sought to work with the public library and its grounds to make the project a reality. They invested their energy and connections to prepare the site and to retain the commitment of volunteers after the first work day. Volunteers enhanced their personal skills and grew community relationships. Partnerships formed through the seed-saving project and multiple community capital investments added critical human, political, and nancial assets that helped the garden evolve into a food forest and enhanced environmental services for the town.

Beacon Food Forest – Seattle, WA

One of the most visible and well-known community food forests in the United States holds that distinction not necessarily by choice. A media barrage in the midst of planning vaulted the Beacon Food Forest onto the international stage, leading to extensive publicity on the project itself and food forest concept more generally. Somewhat unexpectedly, leaders found themselves beset by numerous requests for interviews and site tours, which posed a serious challenge because no plants were even in the ground yet! At the same time, however, the Beacon Food Forest demonstrated that due diligence and perseverance before fame is crucial for weathering exposure and managing the unforeseen.

The swell of attention increased the Friends of Beacon Food Forest’s resolve, and as the stories of their food forest filtered through the media, important public dialogue ensued among people responding and reacting to online articles and news outlets. The feedback illuminated ideas that needed further thought. For instance, the P-Patch program, along with other community garden programs, offers one plot per family or individual, which is a different model than growing food collectively as a community in an area open to everyone, regardless of whether they helped tend, harvest, or manage the site. Through this public dialogue, Beacon Hill stakeholders came to see a real need and desire within their own group to lead a truly public, community food resource rather than a set of community garden plots distributed to lucky recipients. The Friends of the Food Forest realized they would need to take a look at policies that could potentially affect a public food park rather than a community garden. They knew that in order to enact communal management, the public would need a sense of ownership of the project.

The Bloomington Community Orchard – Bloomington, IN

Bloomington’s parks and recreation department houses the forestry division, which is responsible for the city’s urban canopy and proudly maintains its status as a Tree City USA. In January 2010, Lee contacted Amy with an offer of $2,000 from the department and a location near the Willie Streeter Community Gardens in Winslow Woods Park. The park is home to a large baseball field, basketball court, nature trail, and playground and has a large shelter for community events. Bloomington’s largest community garden, the Willie Streeter Community Gardens, has been at the park since 1984. The garden hosts conventional and organic garden plots and raised beds for a total of 178 spaces. Burney was part of a network of local government officials and introduced the community orchard idea through conversations with other community members. Amy did not expect the response she received from the parks and recreation department, but she immediately reached out to close friends, colleagues, and scholars at the university to find allies who would be interested in helping her. She also asked those who were curious to attend and provide support at the first public meeting she organized. This meeting set initial support in motion for BCO and opened the door for a network of like-minded people.

Recent Articles

Oxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreSo you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start? Learn how to break down the options of harvesting tools!

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read MoreEver heard the phrase, “always follow your nose?” As it turns out, this is a good rule of thumb when it comes to chicken manure. Composting chicken manure in deep litter helps build better chicken health, reduce labor, and retain most of the nutrients for your garden. The following is an excerpt from The Small-Scale Poultry…

Read More