Badlands without Beavers: How Teddy Roosevelt became a conservationist

There’s no doubt that beavers offer huge support to various ecosystems. Even Teddy Roosevelt learned that when on a hunting trip to beaverless badlands turned out disappointing. This experience was enough to turn him from naturalist to conservationist. Read the full story and you too will become a “Beaver Believer.”

The following excerpt is from Eager by Ben Goldfarb. It has been adapted for the web.

In November 1887 a twenty-nine-year-old politician named Theodore Roosevelt embarked on a five-week-long hunting trip into North Dakota’s badlands, a lonesome range of alien buttes and endless skies. The badlands had for years been Roosevelt’s sanctuary, the sacred terrain, said the New York native, upon which “the romance of my life began.” It was in the badlands that Roosevelt metamorphosed from an asthmatic urbanite to a strapping cowboy, where he learned to run cattle and shoot game, where the rough-and-tumble mythology of the future president was born and burnished. And it was to the badlands that Teddy retreated after his mother and his first wife, Alice, died within twelve hours of each other in February 1884, a day Roosevelt mourned in his journal by scrawling, “The light has gone out of my life.” North Dakota’s spartan beauty and tough living—the oceanic plains, the trilling meadowlarks, the exhausting days and crisp nights—rekindled Teddy’s joie de vivre.

retreated after his mother and his first wife, Alice, died within twelve hours of each other in February 1884, a day Roosevelt mourned in his journal by scrawling, “The light has gone out of my life.” North Dakota’s spartan beauty and tough living—the oceanic plains, the trilling meadowlarks, the exhausting days and crisp nights—rekindled Teddy’s joie de vivre.

By his 1887 hunting trip, though, Roosevelt’s prairie paradise had gone dark.

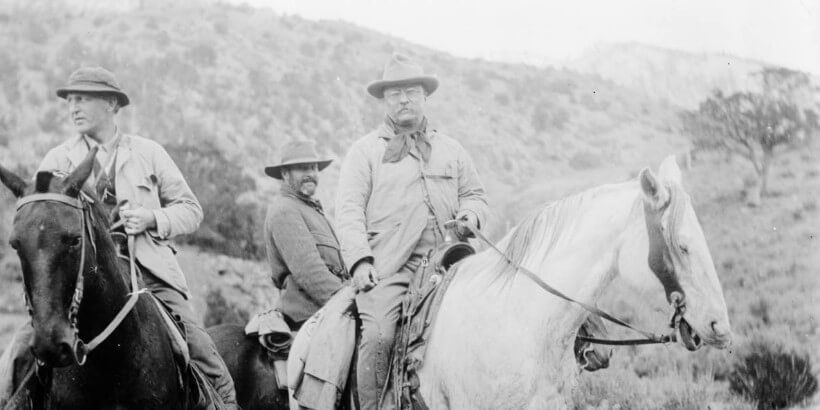

For three weeks Teddy—still skinny, but already sporting his trademark mustache, toothy grimace, and bespectacled squint—rode solo through the badlands, scanning for wildlife. He saw little. Elk, grizzly, and bison had vanished, and bighorn sheep and pronghorn grown scarce. Migratory birds had forsaken the Little Missouri Valley. The trigger-happy Roosevelt still bagged eight deer, four antelope, and a pair of sheep, but it was clear that his beloved landscape had slipped out of whack.

What had befallen the badlands?

A wild mammal had been replaced by a domestic one. “There were so few beavers left,” wrote Edmund Morris in The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, “. . . that no new dams had been built, and the old ones were letting go; wherever this happened, ponds full of fish and wildfowl degenerated into dry, crack-bottomed creeks.” The devolution was accelerated by the encroachment of cattle, which “eroded the rich carpet of grass that once held the soil in place. Sour deposits of cow-dung had poisoned the roots of wild-plum bushes, so that they no longer bore fruit; clear springs had been trampled into filthy sloughs; large tracts of land threatened to become desert.”3

The sight pained Roosevelt, who, as a hunter and rancher himself, must have recognized his own culpability in razing the prairie. Back in New York, he convened a cabal of influential animal-lovers to “work for the preservation of the large game of this country,” a group that later became the Boone and Crockett Club.4 Roosevelt had always been a naturalist, but it was that mournful badlands trip that helped turn him into a conservationist. Seeing a landscape without its beavers can do that to a guy.

Teddy’s seminal badlands experience provides a stark illustration of how badly cows and beavers tend to coexist. American ranchers own 120 million acres of private land and hold grazing leases on more than a quarter-billion public acres; where cattle roam, beavers are often scarce. That’s partly because unchecked grazing, as Roosevelt discovered, demolishes streamside habitat,  and partly because most ranchers consider the rodents irrigation- clogging, tree-felling, field-flooding menaces. “I like trees and I like cattle,” Jonathan Knutson, a columnist at the trade journal AgWeek, griped in a 2016 screed titled “Nature’s Engineers? Or Nature’s Despoilers?” “In my personal experience, that leads—inevitably and unavoidably—to being none too fond of beavers.”5

and partly because most ranchers consider the rodents irrigation- clogging, tree-felling, field-flooding menaces. “I like trees and I like cattle,” Jonathan Knutson, a columnist at the trade journal AgWeek, griped in a 2016 screed titled “Nature’s Engineers? Or Nature’s Despoilers?” “In my personal experience, that leads—inevitably and unavoidably—to being none too fond of beavers.”5

Hanes Holman is proof that there’s nothing inevitable or unavoidable about detesting beavers.

Holman, the manager of Elko Land and Livestock Company, is a thoughtful, amiable stockman fond of uttering provocative chestnuts like “We live in a world that is totally governed by time.” I met Holman near a cattle yard in Elko County, Nevada—when I listened later to my recording of our conversation, I could barely make it out over the lowing of black Angus cows—not far from the PX Ranch, where he’d worked as a hand soon after graduating high school.

“I remember on the wall at PX, we would nail up beavertails, show how many we caught,” he told me as we sat in a cottonwood’s shade. “We had beaver everywhere. The irrigators were angry all the time. In the evening you went out and trapped beaver. It was just part of life, and you didn’t know any better. My dad hated beaver, his dad hated beaver. That’s what you did as a rancher—you fought beaver.”

As Holman’s understanding of riparian ecosystems evolved, so did his appreciation for aquatic rodents. Water is a Nevada rancher’s most important asset, and any force capable of capturing and retaining it is a godsend. Now, Holman told me, “I’m probably one of the biggest advocates of the beaver.” He’s far from the species’ only admirer in Elko County, where a series of promising grazing experiments suggest that beavers could become staunch agricultural allies. For that to happen, though, livestock producers—as tradition-bound a community as there is in the West—will have to reconsider their relationship with their aquatic nemesis.

“Half the industry is still on the other side of the fence, and you’re never gonna get ’em all,” Holman told me. “Just two months ago I had a pissed-off irrigator in my office who wanted to borrow a gun so he could get his beavers out of a culvert.”

“Man has got a real bad way of trying to impose his will on nature.”

Parachuting beavers?!

An Idaho historian uncovered 1950s footage of a bizarre wildlife experiment when beavers were packed into travel boxes and dropped from a plane. At the time there was an overpopulation of beavers in some regions and the department of fish and game came up with this creative solution.

The Idaho Historical Society restored the footage and the film in its entirety can be viewed at YouTube

Recent Articles

The fig tree is more than just a fruit-bearing wonder. The complex nature of these trees is beyond fascinating. They are the ultimate ecosystem superheroes!

Read MorePumpkins: Halloween symbol or sweet treat? But have you ever wondered how they became a holiday staple? Discover the rich history behind this fall favorite!

Read MoreHave you ever wondered why fig trees are considered a symbol of abundance and fertility across cultures? What exactly makes these trees so special?

Read MoreSeeds strengthen our connections to what we grow and eat; they are intrinsic to our identity and our future. I cherish seed as a common resource that all the world should be able to access freely.

Read MoreCultivating mushrooms on various substrates has many benefits — from composting, mycoremediation, and creating value-added consumer goods. It helps reduces waste and helps the environment!

Read More