Agroforestry Versus Permaculture: Which Approach to Use for a Community Food Forest

Ok, so we’ve gone over some basics of community food forests: Now it’s time to figure out how to plan one. There are two schools of thought on the best approach to building a community food forest: agroforestry or permaculture.

The former offers a science-based approach while the latter incorporates elements of social design. Both work well on their own, however, it doesn’t have to be an either/or situation as explained in The Wetherby Edible Forest example.

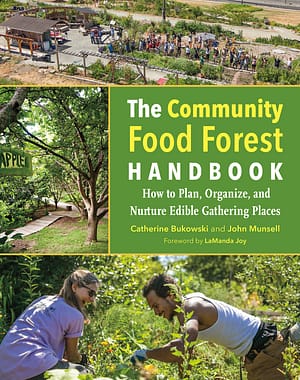

The following excerpt is from The Community Food Forest Handbook by Catherine Bukowski and John Munsell. It has been adapted for the web.

Which Approach to Use?

One way to think about the difference between agroforestry and permaculture is that agroforestry is a discipline and permaculture is a worldview. Agroforestry is a set of scientific practices designed to achieve financial and environmental goals.

Permaculture practices are largely based on environmental observations and ideas about nurturing relationships between the land and people.

Using one or the other approach when designing a community food forest will lead to slightly different planning and management decisions.

So, what do agroforestry and permaculture look like in a community food forest?

Permaculture can provide vast and growing stores of human energy in the form of volunteers and project leaders from broad networks.

Many people practice permaculture, and it continues to grow in popularity. Use of permaculture practices such as forest gardens, water catchment (a piped water system), and zones and sectors can shape the overall layout and visual quality of a community food forest.

Agroforestry provides the science that can help with technical design and maintenance strategies of a food forest project—how to manage combinations of trees, shrubs, and crops.

Some agroforestry researchers are interested in studying community food

Polyculture plantings are designed to connect across a site until the landscape resembles a young woodland, as shown here at the Beacon Food Forest. This site receives a great deal of precipitation and can support abundant varieties of fruit trees and other species grown in close proximity

forests, and their involvement can help increase the competitiveness of a project when it comes to winning technical grants and assistance.

Much of the information taught through permaculture comes from scientific fields, but only in the last few years has formal research been initiated to better understand the practices.

Agroforestry, on the other hand, has a robust record of researching plant interactions in order to suggest detailed management plans and economic viability.

Permaculture design places emphasis on the relationships between plants as well as their resources, such as soil-to-plant interaction.

Permaculture design principles are helpful in organizing site layout in an effective, efficient, and accessible style.

Existing site elements and ease of use help determine placement of recreation areas, spots for community activities, and food-production areas.

Learning about agroforestry can help project managers better understand ways to manage plant and tree interactions.

Combining permaculture and agroforestry in the planning, design, and management phases of a community food forest allows project leaders to create a project vision that is both practical and competitive from the standpoint of human resources, project funding, long-term maintenance, and policy making.

The extent to which the two can be assimilated depends upon the nature, needs, and backing of a community food forest project, but project leaders should consider the role both can play in achieving their goals.

Both disciplines are adaptable, and adaptability is critical in a community food forest because the demands of intercropped trees and plants change over time across unique site conditions.

Permaculture design guidelines like zones and sectors help in deciding where to place particular plantings, built elements, or other features. After locating the best places for specific sections of a design, agroforestry guidelines can be used to determine specific botanical configurations that have been tested and are known to produce results.

For example, deciding on the location for a barrier to wind, dust, or street debris uses permaculture guidelines.

Agroforestry can provide the specific planting configuration of creating an A-shaped barrier with two rows of short, thick bushes divided by a row of taller trees between them.

Accompanying calculations estimate the area that will be protected from wind based on the height of the tree row. Additionally, agroforestry provides details on potential maintenance needs and management plans, such as pruning and thinning.

The 18th and Rhode Island Permaculture Garden in San Francisco, California is located on a 14 percent slope. Rock supported terraces and mulch pathways built on the contours help manage water and store it on site. The terraces also raise food growing areas away from the path and small signs like this one provide a reminder to clean up after pets. Encouraging people to wash produce before consuming it is also a best practice.

The differences between the two disciplines can also be exploited to support the practical facets of a community food forest.

Knowledge of agroforestry can help when defining the purpose and composition for particular plantings. It can fine-tune relationships between species with science-based management.

Permaculture can aid in conceptualizing the design for particular plantings using social factors to help determine species.

For example, one area might be planted with species that are used by a specific ethnic population to create a space where they feel invited to harvest and celebrate.

Permaculture is also rich with design formulae and palettes drawn in compelling detail, with clear influence from the landscape architecture field.

Locating a community food forest on public property sometimes requires approval of the design by a certified landscape architect to meet city regulations.

A detailed permaculture drawing can make it easier to share site design concepts with landscape architects because it uses a format familiar to them when finalizing plans to meet city codes and the community’s vision.

Though there are differences between agroforestry and permaculture, clear similarities they share are a fundamental emphasis on the whole environment and incorporation of traditional ecological and contemporary ethnobotanical knowledge.

Both also integrate trees, crops, and livestock on the same piece of land and both recognize potential connections to people, places, and community development.

Both promote beneficial plant communities that minimize competition and distribute resource demands, recycle nutrients, fertilize the soil, and effectively grow together over time.

They hold the attention of progressive people seeking to creatively design sustainable and resilient land use systems at various scales. The Wetherby Edible Forest in Iowa City is a useful example of an adaptive approach that integrates agroforestry and permaculture.

The Wetherby Edible Forest

The Wetherby Edible Forest in Iowa City was created in 2011 through a grant partnership between a nonprofit organization called Backyard Abundance and the Iowa City parks and recreation department.

The food forest began as an orchard-inspired edible maze on barely a sixth of an acre.

The goal was to increase educational opportunities at parks in the city and introduce youth to local urban food production.

The organization holds public seminars, hands-on training, design consultation, and public demonstrations throughout Iowa City and surrounding areas.

By 2014, the Wetherby Food Forest had doubled in size and transitioned into a full food forest focused largely on agroforestry education.

Fueling the growth of the Wetherby Food Forest was the financial support received from the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship Specialty Crop Block Grant Program.

Volunteers installed edible perennials as a demonstration for regional farmers as well as a base for pollinator habitat.

A key deliverable of the specialty crop project was the Edible Agroforestry Design Templates Manual. It showcased replicable designs and provided instructions for site assessment.

It also made species suggestions for alley crop orchards, edible forest edge projects, shady edible forests, edible riparian buffers, edible windbreaks, homestead orchards, and silvopasture. The manual is free and available to download at www.backyard abundance.org.

Permaculture is a source of inspiration at Backyard Abundance and a driving force behind initiatives such as the Wetherby Edible Forest.

Agroforestry found its place in terms of partnerships and publications for specific land use demonstrations and technology transfer at the site.

Farmers learned about agroforestry, which helped create a clear connection to institutional funding sources through its science-based practices.

Altogether, this example not only showcases the possibility of generally blending permaculture and agroforestry but highlights a specific way these practices can be simultaneously leveraged in support of a community food forest and associated organizational partnerships.

The history of the Wetherby Edible Forest shows that the question of scale is a key consideration for sustainability.

In hindsight, Backyard Abundance and Iowa City Parks and Recreation, which recruit volunteer maintenance for the food forest, determined that one of the most important lessons learned was to start small and grow over time.

In order to receive funding for agroforestry demonstrations, the site had to be at least one third of an acre, but following through on developing even one sixth of an acre proved difficult in light of the extent of community support they were able to generate.

With an honest assessment of capacity in mind, an organization or collective of community members working on a community food forest project can selectively pursue grants with realistic and achievable requirements.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Oxeye daisies are one of the most important plants for pollinators including beetles, ants, and moths that use oxeye daisies as a source of pollen and nectar. Instead of thinking about removing a plant like oxeye daisy, consider how you can improve the fertility and diversity of habitat resources in your home landscape, garden, or…

Read MoreSo you want to start reaping your harvest, but you’re not sure where to start? Learn how to break down the options of harvesting tools!

Read MoreWhat’s so great about oyster mushrooms? First, you can add them to the list of foods that can be grown indoors! They are tasty, easy to grow, multiply fast, and they love a variety of substrates, making oyster mushrooms the premium choice. The following is an excerpt from Fresh Food from Small Spaces by R. J.…

Read MoreEver heard the phrase, “always follow your nose?” As it turns out, this is a good rule of thumb when it comes to chicken manure. Composting chicken manure in deep litter helps build better chicken health, reduce labor, and retain most of the nutrients for your garden. The following is an excerpt from The Small-Scale Poultry…

Read More