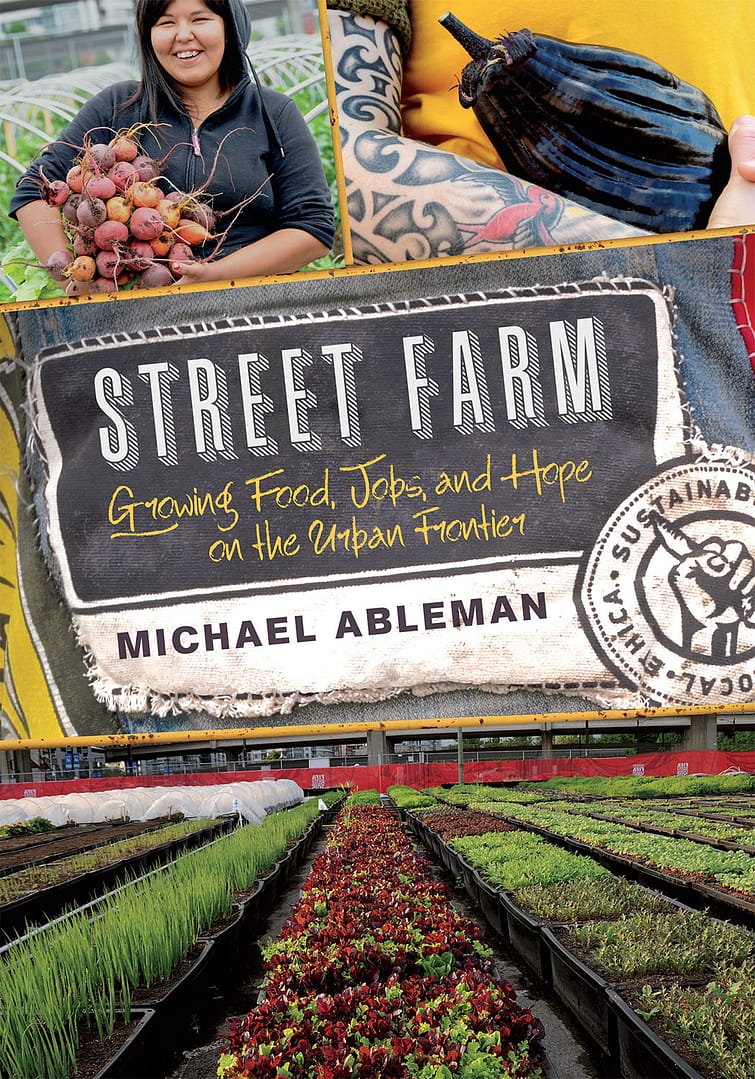

Street Farm

Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier

Street Farm is the inspirational account of residents in the notorious Low Track in Vancouver, British Columbia—one of the worst urban slums in North America—who joined together to create an urban farm as a means of addressing the chronic problems in their neighborhood. It is a story of recovery, of land and food, of people, and of the power of farming and nourishing others as a way to heal our world and ourselves.

During the past seven years, Sole Food Street Farms—now North America’s largest urban farm project—has transformed acres of vacant and contaminated urban land into street farms that grow artisan-quality fruits and vegetables. By providing jobs, agricultural training, and inclusion in a community of farmers and food lovers, the Sole Food project has empowered dozens of individuals with limited resources who are managing addiction and chronic mental health problems.

Sole Food’s mission is to encourage small farms in every urban neighborhood so that good food can be accessible to all, and to do so in a manner that allows everyone to participate in the process. In Street Farm, author-photographer-farmer Michael Ableman chronicles the challenges, growth, and success of this groundbreaking project and presents compelling portraits of the neighborhood residents-turned-farmers whose lives have been touched by it. Throughout, he also weaves his philosophy and insights about food and farming, as well as the fundamentals that are the underpinnings of success for both rural farms and urban farms. Street Farm will inspire individuals and communities everywhere by providing a clear vision for combining innovative farming methods with concrete social goals, all of which aim to create healthier and more resilient communities.

Reviews and Praise

Choice-

"This work is an engaging personal narrative about the creation of Sole Food Street Farms, a small-scale urban farm with several locations in the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver, British Columbia—one of the poorest urban areas in North America. This book discusses urban blight, human misery, and, in an astonishing juxtaposition, organic farming. It describes the challenges and rewards of farming in a place where poverty, drug addiction, and crime are prevalent; it also describes a location where concrete and asphalt cover the ground, and the soil underneath is polluted by a century of industrial and other urban use. The book is filled with colorful photographs of people and farms. The popularity of this 'hot topic' alone will make this work attractive to a wide array of academic libraries serving undergraduate populations. It is strongly recommended for academic and public libraries in British Columbia and for all public libraries that service either rural or urban populations. Summing Up: Highly recommended. Lower-division undergraduates and general readers.”

More Reviews and Praise

“Most of the world’s people live in cities, and Street Farm is a story of how to bring cities back to life, literally and emotionally. The cold, forbidding landscapes of urban life bring our hearts to a standstill. When streets, medians, abandoned land, parks, and byways are transformed by soil, bugs, microbes, pollinators, and seeds, lives bloom. Connectedness flourishes, and people become denizens once again.

“Local food is not a mere talisman or gesture. We localize food webs near our homes for identity, nourishment, and taste. Taste is a sense, but it is also a common sense. Local food not only addresses quality of life, economy, and food security, it changes our hearts. Michael Ableman has a finely honed sensibility. Read how he gardens society, grows well-being, weeds out despair, and sows hope in this wonderfully written testament to life.”--Paul Hawken, author of Blessed Unrest

“Whenever Michael Ableman sees a barrier, he runs over and kicks it in. Lucky for us, this strikingly focused anarchist writes about it too, sharing the deeply moving story of reclaiming land and building real community in the most unlikely places, from the ground up. Read this book and be amazed.”--Dan Barber, chef/co-owner, Blue Hill and Blue Hill at Stone Barns; author of The Third Plate

“Michael Ableman is an innovator extraordinaire whose projects have a track record of benchmarking new models of best practice. He is one of the handful of inspiring visionaries on the planet who are redefining our future food systems.”--Patrick Holden, founding director, Sustainable Food Trust

“In this inspiring book, Michael Ableman documents that generating paradise by growing vegetables amidst the urban jungle also rehabilitates lost souls, builds community, and creates genuine economic value. Street Farm is a great antidote to pessimism, illustrating how even seemingly broken people can contribute to themselves, to society, and to our shared ecology.”--Gabor Maté, MD, author of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts

“Street Farm tells it like it is on a gritty urban farm, introducing us to rough but real people who learn to live again through growing food and nurturing the soil. Michael Ableman shows us that we can amend distressed soils and distressed communities alike.”--Novella Carpenter, author of Farm City

“Michael Ableman recognises that urban growing is not just about producing lovely, healthy, local food. It’s about creating meaningful work that pays a decent living and showing that the cities where most of us now live can play a vital role in building a better, more resilient food system. In Street Farm, Ableman writes about many of the issues that we also grapple with as we strive to build a better food system in London. Sole Food Street Farms is an uplifting demonstration of how communities really can change the world: inspiration for all those who feel they might be too small or powerless to make a difference.”--Julie Brown, director, Growing Communities

“Michael Ableman examines the heart and soul of urban agriculture through the eyes, hands, and hearts of people in need of a place of civility and serenity. The passion and humility of the farmers who work at Sole Food Street Farms in Vancouver shines through. They are neighborhood folks, many with transgressions of addictions, who find solace in farming.

Ableman strongly believes that farming must be grounded in an economy in which food has value and so do the people who grow it. From Street Farm, we learn that urban agriculture indeed takes a village of planners, politicians, investors, and believers to envision such an economy, with urban agriculture as the new economic engine providing jobs, feeding families, and building communities.”--Karen Washington, urban farm activist; co-founder of Black Urban Growers

“This is the most inspiring book I have read in years. I found myself trembling at the monumental challenges that Michael Ableman and his colleagues faced and overcame in creating a set of urban farms in some of the most downtrodden neighborhoods on the continent. This is a story of hope, disappointment, and hope returning, detailing the mistakes and setbacks as well as the victories and benefits of creating a large-scale food-growing program in a big city. It shows us how far we have yet to go to provide healthy food to any city’s underprivileged, but inspires us with the progress that Ableman and others have made. Told in moving vignettes and full of useful tips for those who want to try to heal the urban food grid, this is an important book. It’s essential reading for everyone in the urban food movement.”--Toby Hemenway, author of The Permaculture City and Gaia’s Garden

“Sole Food Street Farms is living proof that creative social enterprises, thoughtful land use, and green jobs can combine to make cities more inclusive and resilient. Michael Ableman’s work and passion helped make Vancouver a global leader in urban food systems, with happier and healthier people.”--Gregor Robertson, mayor, Vancouver, British Columbia

Sierra Magazine-

“A compelling tale…filled with touching characters, conflict, and ultimately, redemption.”

“In a publishing world where trivial passing thoughts are blogged into barely passable books, it is a serious pleasure to come upon a warts-and-all account of a deeply important enterprise. In Street Farm, long-time farmer Michael Ableman reports on the triumphs and failures of Vancouver’s Sole Food Street Farms. The goal of this five-acre network of four farms—begun in the poorest postal code in Canada—is to produce, from thousands of boxes of planted dirt, not just delicious food but salvaged lives. Candid about the difficulties of creating flourishing farms on hot pavements and of making reliable farm workers of dispirited locals who struggle not only with poverty but with assorted personal demons, Ableman has written an important, inspiring, and bravely honest book.”--Joan Gussow, author of Growing, Older and This Organic Life

Publishers Weekly-

"In this insightful, inspiring narrative, Ableman explains that he had been a farmer for 40 years when he decided to attend a meeting in an urban slum in Vancouver, British Columbia, called Low Track. That meeting and several more resulted in Sole Food Street Farms, which is currently operating four urban farms in downtown Vancouver. Those interested in starting their own neighborhood or urban garden will deeply appreciate his insight into urban farming’s unique challenges and opportunities. Those serious about embarking on a similar endeavor will find a mix of inspiration and solid advice they’ll want to keep close at hand.”

“From skid row to rows of food: Michael Ableman’s interwoven growing skills and people empowerment are beautifully illustrated here by ‘ground zero’ spaces transformed to market gardens. His long experience of creating non-profit urban farms has borne fruit in Vancouver, BC. Sole Food Street Farms produces twenty-five tons of food every year, grown in unlikely places by drug-addicted farmers, softened in the process like the soil they tend. Ableman acknowledges it’s an imperfect endeavour, but these gardens offer hope: ‘Food’s the next thing, man!’”--Charles Dowding, no-dig organic market gardener; author of How to Create a New Vegetable Garden

“I have known Michael Ableman for over twenty years. He is one of the pioneers of small-scale urban farming, growing quality food for urban communities. He has worked through the challenges inherent to urban farming and is a premier trainer in the industry. Michael has been and is an inspiration to myself and many urban agriculture leaders around the country and the world.”--Will Allen, founder and CEO, Growing Power