It All Starts with a Seed: The Art & Joy of Collecting Seeds

Gardening’s greatest magic: one tiny seed transforms into a mighty plant!

Collecting seed is one of the great pleasures of the gardening year. Read on for getting started in collecting seeds in your garden.

The following is an excerpt from The Ecological Gardener by Matt Rees-Warren. It has been adapted for the web.

Collecting Seeds: Getting Started

Collecting seed is easily one of my favourite gardening tasks, as I love to look at the minuscule seeds in my hand and wonder how nature transforms from just one seed into the mature plant standing before me.

Once you have collected the seed, you must decide where you’re most likely to sow it next, as this will influence how the seed should be kept.

In nature, the seed will lie on the ground from the moment it’s released to wait for germination in the spring or maybe even many years hence, until the right conditions arise.

Scattering Seed

We can replicate this by simply broadcasting (scattering) the seed, still attached to the stems, where we wish them to grow without even needing to collect the seed at all – this works well for biennials like foxgloves.

Or, we can collect the seed in the way described in Collecting Seed and choose to either broadcast it in the autumn or hold some back for seeding in the spring. If so, some knowledge of seed dormancy is required.

Weather Considerations

Many wild species produce seeds that depend on particular weather patterns and events in order to germinate at the optimum time for their survival.

These include frosts, heavy rains, low light levels and fluctuating temperatures.

Dormancy is an evolutionary adaptation that prevents seeds from germinating if these conditions are not met, so if we store seeds inside and try to sow in the spring, they won’t produce plants.

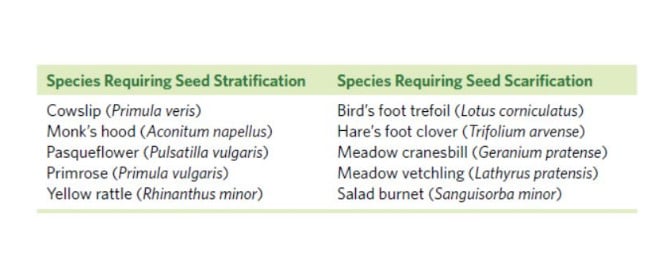

Stratification and Scarification

Therefore we must use a process called stratification in order to replicate this wild dormancy period.

The best way to achieve this is to place the seed within a slightly damp medium, such as very gritty compost or damp paper, seal it in a jar and place it in the fridge or freezer for a period of time – generally 6–12 weeks. Some species require further manipulation, called scarification (see table 3.3).

This involves breaking the hard outer husk of the seed by either cutting or crushing, then allowing the internal embryo to break out and germinate.

Finally, if we are only seeking to store the seed, say until sowing the following autumn, then it’s best to keep the seed completely dry in a sealed jar in the fridge or a dark cupboard.

Sowing Seeds

Collecting seed is one of the great pleasures of the gardening year.

If the seed has been through the aforementioned processes, then come late winter or early spring it can be sown into pots or trays in a greenhouse or on a windowsill. If the seeds are small, then broadcasting them into trays is the most effective.

When they break through and form seedlings, you can thin out around half to allow the others to grow strong and healthy. As these seedlings grow bigger, tease out and place them into a small pot to grow on further.

If the seeds are large enough to handle individually, place them one by one into small pots and grow on until they can be transplanted into larger pots or out in the ground.

Remember to use low-nutrient soil in the beginning and move progressively up into higher nutrients as the plants progress – for example, from leafmould and sand to compost and loam.

Collecting Seeds

Collecting seed isn’t as easy as it seems; it takes timing, experience and judgement to collect at the perfect stage of ripeness.

1. Once the plant has flowered, watch for the stem and the seedhead to brown and ripen.

2. Collect on a dry day. Cut the whole stem off with the seedhead attached and place in a paper bag or something similar.

3. Take the stem inside and carefully extract the seeds on a table with white paper spread out on top – seeds can be small so the paper will help you detect them when they fall.

4. Once you have released all the seeds, collect them up and place them in small envelopes or sachets, then label them.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

When you save seeds, you become a plant breeder! Take control of your seeds and grow the best traditional and regional varieties and even develop your own.

Read MoreSave seeds, save the future! Embracing the tradition of saving seeds is a powerful practice for both home gardeners and seasoned horticulturists alike. Take control of your garden’s destiny – start saving seeds today!

Read MoreDid you know the Netherlands is a global agricultural powerhouse? Despite their size (two-thirds the size of West Virginia) they’re #2 in exports behind the US. Their secret? Innovative greenhouses and hoophouses are changing the game!

Read MoreDitch the big garden myth! 🌱 Think you need an outdoor garden to enjoy fresh produce? Think again! Follow our quick & easy guide to harvest vibrant greens at home in just a couple of weeks, no matter your space.

And cold temperatures doesn’t have to mean the end of fresh greens. You can enjoy vibrant greens year-round!

Read MoreGet ready for a bountiful harvest! Storing seeds is the key to having a successful growing season. Follow these tips to keep your seeds organized and ready to plant 🌿🪴 Get ready to plant like a pro this season!

Read More