Pass the Walnut Syrup?

Everyone knows and loves maple syrup, and in some states (like Chelsea Green’s home state of Vermont), it’s big business.

However, it’s a widespread myth that maples are the only trees that can be tapped to produce sap, according to Michael Farrell, sugarmaker and director of Cornell University’s Uihlein Forest. Sap can also be collected from birch and walnut trees. And these three tappable species can be found in every state except Hawaii (where people collect sugary sap from palm trees).

The following is an excerpt from The Sugarmaker’s Companion by Michael Farrell. It has been adapted for the web.

The Walnuts (Juglans spp.)

There are 21 species within the Juglans genus that occur throughout the world. The two most common ones found in the eastern United States are black walnut (Juglans nigra) and butternut (J. cinerea). Very few people know that walnuts produce sap and hardly anyone is currently tapping these trees, though I expect that will change in the future. There has been some interest in “sugarbushing the black walnut” among nut growers to yield yet another great product from these amazing trees, yet very little walnut syrup has actually been produced.12 I highly encourage you to try making syrup from these trees, with one word of caution. Walnut syrup comes from nut trees, and while this may seem obvious to you, some folks may not make that connection. Since there are many people allergic to tree nuts, it is possible that someone could also suffer allergic reactions from consuming walnut syrup. Therefore, be sure to take extra precautions if you plan on providing your walnut syrup to others, either as a gift or for sale. I was not able to find any regulations pertaining to walnut syrup, but food safety specialists in Ontario believe that the boiling process would denature and destroy any allergenic nut proteins if they are present in the sap. Without any peer-reviewed literature documenting this, I would still just use common sense and make sure that anyone who consumes walnut syrup is fully aware that it comes from a nut tree and may cause problems for those with severe nut allergies.

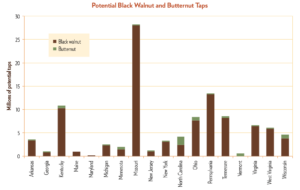

Figure 4.27 shows the number of potential black walnut and butternut taps in the eastern United States. Although there are not nearly as many walnut trees as there are maples, there are enough black walnuts growing in many states to develop cottage industries in walnut syrup production. In fact, many of the mid-Atlantic and midwestern states that don’t have a lot of maples do have a significant resource of black walnuts. Butternuts are much less common than black walnuts, so the opportunities to tap this species will be quite limited. It is worth noting that these figures only include walnut trees growing on forest stands that are at least 1 acre in size and do not include those found in yards, parks, and hedgerows (where I often see them growing).

FIGURE 4.29. The black splotches with whitish margins are indicative of cankers on butternut trees. Photo courtesy of Manfred Mielke, USDA Forest Service, bugwood.org

Butternut (juglans cinerea)

Also known as white walnut, the butternut is usually recognized for its edible nuts and beautiful lumber. One of its lesser-known qualities is that it produces a delicious sap that can be drunk fresh or boiled down into syrup. Butternut sap generally contains about 2% sugar and flows at the same time of year as maples. The syrup is quite delicious—many people have described it as having nutty and almost fruity overtones. (Watch a video of Michael Farrell tapping a butternut tree.)

Butternuts are much less common than black walnuts, so the opportunity to tap this species is limited. If you do decide to tap a butternut, there is one thing to be aware of: a jelly-like substance regularly appears in the sap and should be filtered out. Otherwise, it becomes even more concentrated. The pectin that produces this consistency isn’t something to be concerned about (it’s often used as a gelling agent in jams and jellies), but it should be dealt with if you don’t want to end up with butternut jelly.

To tap the tree, Farrell recommends using one 5/16” spout per tree and minimizing any vehicular traffic around the root system. You may want to start with a few butternut trees to see how they respond before tapping the rest. And if you can beat the squirrels to the nuts, gather them for planting. Butternuts are fast growing and can easily be started by planting a nut in the ground and protecting the emerging seedling from rodents, deer, and lawn mowers. Butternuts are increasingly rare due to the spread of a fatal disease called butternut canker, so planting new trees could help perpetuate this important yet declining species.

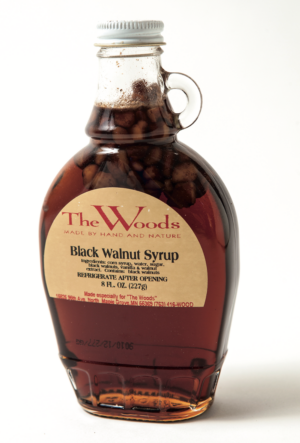

Maple syrup is not only the only species that has a fake syrup substitute. This “black walnut syrup” is actually just corn syrup, cane sugar, and walnut extract with pieces of black walnuts added. Photo by Nancie Battaglia

Black Walnut (juglans nigra)

Black walnut trees are somewhat rare in the Northeastern U.S., but are more common in Appalachia and the Midwest. They have a reputation as one of the most valuable timber species due to the beautiful color, strength, and durability of their lumber. What is not well known is that they yield a sweet sap at the same time of year as the maples. Even if you don’t like the taste of black walnuts, chances are you’ll love black walnut syrup.

With black walnuts, it may be best to tap smaller-diameter trees with a lot of sapwood rather than large old trees that contain mostly heartwood. (Only the white sapwood near the bark will produce sap – hence the name.) Smaller trees between 6 and 10” in diameter cannot be harvested for saw-logs, so you can gather sap for many years until they grow into sawlog size, if your intention is to use them for lumber.

No matter what size of black walnut trees you tap, you should expect them to yield much less sap than maples (or butternuts). The sugar content is comparable to that of maples, yet the volume seems significantly lower, possibly because there’s very little sapwood on the outside of the tree. Research is currently being conducted to determine the sugar content and quantity of sap that can be obtained from tapping at different intervals during the dormant season, but in the meantime, Farrell recommends conducting your own experiments to see when walnut sap flows best on your property.

The flavor of black walnut syrup is surprisingly similar to a light or medium amber maple syrup, but with more butterscotch and nutty overtones. After Farrell conducted a workshop on black walnut syrup production in Vermont and offered samples for tasting, nearly all the attendees were making plans to go plant walnut trees. Are you in?

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Tips for Seed Saving · You either have dry seeds or wet seeds. Proper drying & storing is essential so they can germinate months (or even years) down the road.

Read MoreWhen you have a family Cow, you have it all. The cow is the most productive, efficient creature on earth. She will give you fresh milk, cream, butter, and cheese, build human health and happiness, and even turn a profit for homesteaders and small farmers who seek to offer her bounty to the local market or neighborhood.

Read MoreBeekeeping has surged in popularity as more people set up backyard hives. Embrace the buzz and transform your backyard into a thriving haven for bees!

Read MoreWhen you save seeds, you become a plant breeder! Take control of your seeds and grow the best traditional and regional varieties and even develop your own.

Read MoreSave seeds, save the future! Embracing the tradition of saving seeds is a powerful practice for both home gardeners and seasoned horticulturists alike. Take control of your garden’s destiny – start saving seeds today!

Read More